It sounds like the plot of some cop-buddy movie: an anarchic hippie social worker (Snoop Dogg or Owen Wilson) is forced to team up with a straight-laced conservative cop (Clint Eastwood, the Rock). Chaos and hilarity ensue. Life lessons are learned. In this case, it actually happened.

It started decades ago in Eugene, Oregon, where police responses to drug- and mental health-related calls were ending badly. So Eugene tried something different: When one of these emergency calls came in, the city dispatched social workers instead of cops. Thirty years later, the strategy has reduced conflicts between police and the public, and made Eugene a national model for harm reduction-oriented policing.

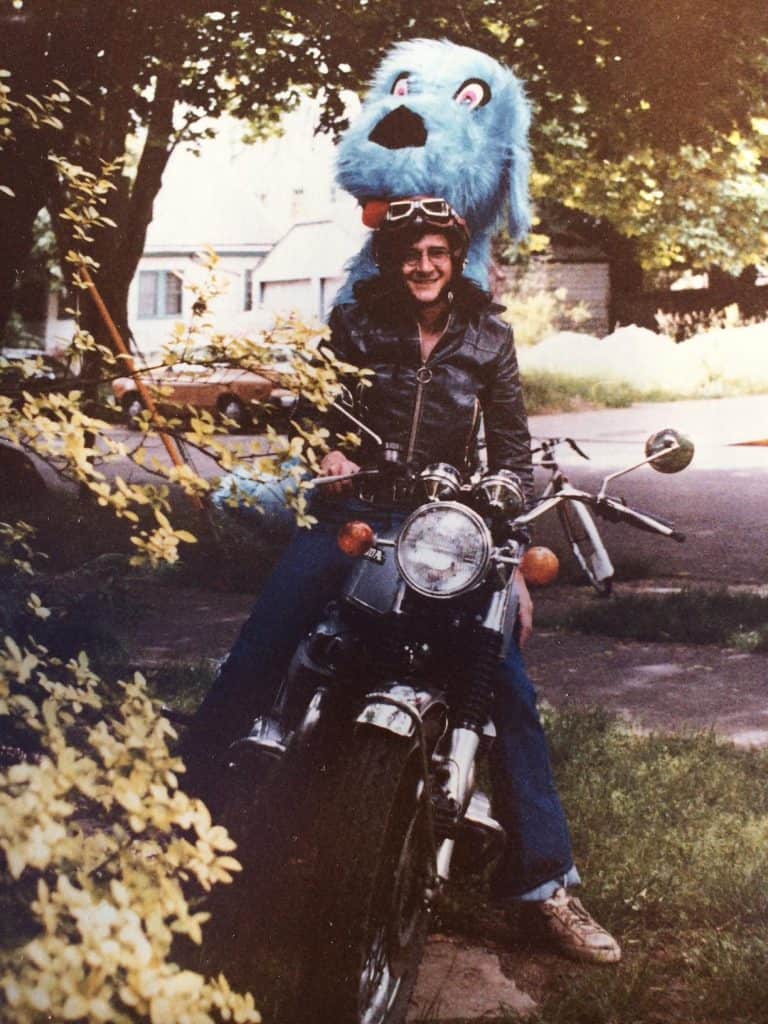

I have fond memories of Eugene. Talking Heads once rehearsed for a tour at the Hult Center there, and on our day off we went to visit the novelist Ken Kesey, who lived nearby. He served us pasta and we helped do the dishes. The city has always had a countercultural streak, and 50 years ago, this mindset inspired some hippies there to create a free clinic and a response team of medics and social workers. They called it the White Bird Clinic.

The White Bird Clinic originally was inspired by a free clinic founded in 1967 in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district that dealt with substance abuse, mental health issues and “rock medicine” — on-site help at concerts and events.

Like that clinic, White Bird focused on the counterculture community that had found a home in Eugene…a community that was often misunderstood by conventional medical and law enforcement institutions. Kids having a bad trip were often given strong tranquilizers like Thorazine by conventional hospitals and clinics. As a result, some of these kids left treatment in worse shape than when they went in. Though initially viewed simply as a crash pad for these kids while they were sobering up, White Bird proved to be successful. And it was free. Anyone that walked in looking for help received it.

Twenty years after it was founded, in 1989, Eugene was experiencing another wave of drug and mental health issues, and the medical and law enforcement establishment didn’t know what to do about it. This became an opportunity — a hail mary pass in the eyes of some — for the clinic and the police department to collaborate. Both sides were trepidatious, but they gave it a try. Non-violent emergency calls that were deemed to require a public health response were routed to the clinic, which was christened CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets).

When it began, CAHOOTS had one beat-up van (the police gave it to them to replace the old Ford Sunbeam bread truck they had been using) and they only responded to calls 40 hours a week. Now they have four vans, about 50 employees and they respond 24/7. CAHOOTS responded to 23,000 calls in 2018.

“Who you gonna call?” It works

It’s easy for me to imagine how differently a drug-related crisis might turn out if a couple of social workers showed up as opposed to a pair of armed police officers. In the view of law enforcement, drug use is a criminal issue, while the clinic folks would tend to see a person in need of help. Very different outcomes as a result.

Roshan Bliss, co-chair of the nonprofit Denver Justice Project, put it this way to the Eugene Register Guard:

“When you’re holding a hammer, every problem looks like a nail. Police are holding hammers, they have paramilitary and legal training. And when you have a schizophrenic young man who is disoriented neither of those hammers are actually applicable.”

CAHOOTS is not officially part of the police department — it is a separate non-profit non-governmental organization. And though CAHOOTS handles around 20 percent of the calls to Eugene’s police, its operating costs are only about two percent of the police budget. The organization saves the city money in other ways, too — for instance, folks that might end up in hospitals are treated by CAHOOTS responders on the spot, saving the city an estimated $8.5 million per year.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.This is not exactly defunding the police, but it’s a way of reappropriating a small percentage of police funding to handle a larger percentage of what used to be police work. Funneling 911 calls regarding suicide, non-violent domestic disputes, mental health emergencies, drug issues and problems unique to homeless folks can be handled by responders specifically trained to deal with such things.

Even the police like it. Responding to these crisis calls consumes substantial police resources and forces the police to engage in situations that they are not completely trained to handle. In these types of situations, encounters with police run the risk of unnecessary escalation that can result in criminal charges or even violence. But that’s much less likely to happen with a response like CAHOOTS. A study found that responses made by a similar program in Denver resulted in no arrests. While it’s hard to know if there would have been arrests if the police had responded, zero is pretty hard to argue with.

Spreading the word

Over the past 30 years, word of CAHOOTS’s success has spread. There’s a nice piece in The Atlantic on CAHOOTS that has moving stories of successful interventions as well as examples of how tragically law enforcement interventions in these areas can end.

Representatives from around 20 cities have visited Eugene to learn about the program. Police reform jumped to the front pages in 2020, and everyone is looking for answers. Representatives from Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Houston, Austin, Chicago, Denver, Portland, Oakland and New York City have all consulted with CAHOOTS. As a result of these visits, Portland and San Francisco have begun pilot programs and Denver has already implemented a similar program called STAR (Support Team Assisted Response). Denver is a much larger city than Eugene, so there were questions as to whether the program would work there, but the results of a recent study show proven evidence of success.

STAR operates very much like CAHOOTS, though so far it is limited in scope, focused on only one troubled area of the city where a lot of people experiencing homelessness live. The six-month study showed that no calls required the assistance of the Denver Police Department and that the on-scene responses took 10 minutes less time (24 versus 34 minutes) than traditional responses. The city felt good enough about its results to allocate $1.4 million to the program, adding four more vans and six two-person teams (a medical person and a crisis worker). They’ll soon expand to responding seven days a week, as happened in Eugene.

Even CAHOOTS recognizes that one can’t simply clone their program. Eugene is only about two percent Black. In more diverse cities, issues of policing, mental health, drug addiction and homelessness are very much connected to racial discrimination, so it’s not as simple as just staffing up and buying more vans. As with White Bird, the responders have to represent and understand the community they are engaged with.

That said, there is reason for optimism. As Denver Police Chief Paul Pazen told CBS News of STAR’s responses: “That’s 748 times fewer that the police department was called, meaning we can free up law enforcement to do what law enforcement is supposed to do, and really what law enforcement is good at: addressing violent crime, property crime and traffic safety. You have a safer community and you have better outcomes for people in crisis.”