It’s noon, and Paimolo Bwalya stops under a mopane tree to lower his heavy firearm and telemetry equipment. He and his colleague have been walking since daybreak in the sweltering Zambian bush, full of dangerous animals, trying to catch a glimpse of the black rhinos that live here.

This is day four of their ten-day patrol in North Luangwa National Park where they monitor the population of rhinos, secure their habitat and protect them from armed poachers. At 40°C (104°F), with the sun approaching its zenith, they can now take a well-deserved rest and eat lunch — today it’s nsima, a meal made of maize, with a dry fish called kapenta.

North Luangwa National Park is one of the last open and intact ecosystems in Africa. Spanning 4,500 square kilometers — about half the size of Puerto Rico — the northern Zambian park is massive. Bwalya, head of the park’s Rhino Monitoring Unit, is one of 440 wildlife police officers and community scouts who monitor it for the elusive animals while watching for evidence of illegal activities: poacher footprints, arson fires, bushmeat drying racks and possession of illegal firearms.

Their efforts pay off in droves. Actually, in herds: In a country that declared black rhinos hunted to national extinction in 1998, today North Luangwa National Park — the only park in Zambia where the animals are thriving — is home to one of the fastest-growing populations on the continent.

The enormity of the task of reviving an extinct species to an area this expansive is hard to overstate, especially a species as physically large as the rhinoceros. Rhino translocations have been undertaken since the early 1960s, but generally they are undertaken over shorter distances and within the same country.

But a series of key decisions around the management of the park have made it an exception, the first of which happened long before reintroduction even began. In 1986, the Zambia Wildlife Authority (now, the Zambian Department of National Parks and Wildlife) joined forces with the international conservation organization the Frankfurt Zoological Society to form one of the first partnerships of its kind in Africa. This collaborative management partnership (CMP), which gave birth to the North Luangwa Conservation Program (NLCP) that exists to this day, did a few key things.

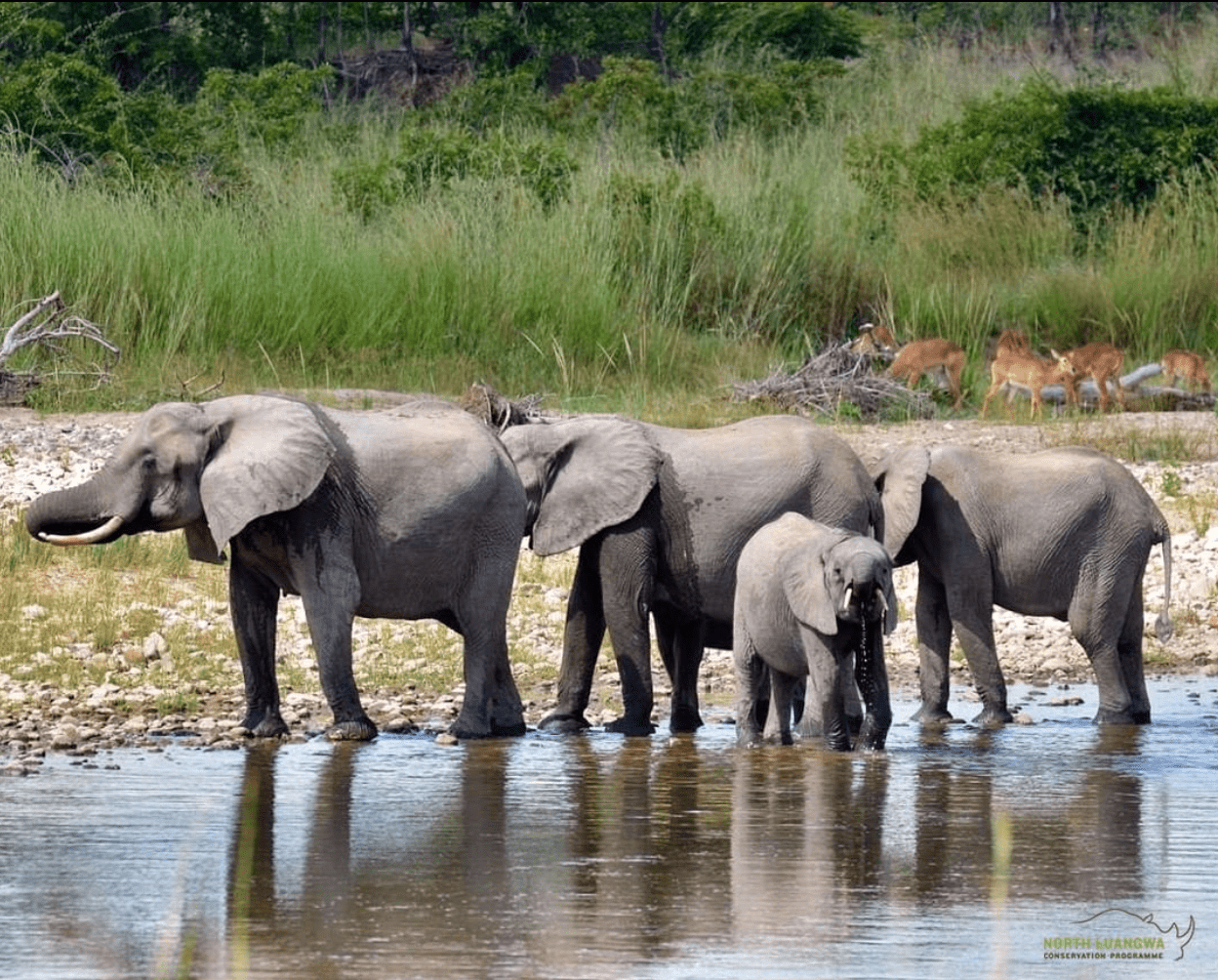

First, it provided financial and technical support to get large-scale poaching under control to an extent that had been impossible under meager national government funding in a park without much tourism. Deploying special intelligence-based protection units, skilled rangers, ecological data monitoring, canine units and even monitoring by aircraft, North Luangwa became the safest national park in Zambia. Elephant populations rebounded and breeding herds settled. Lions and wild dogs made a comeback. Evidence of poaching slowly evaporated.

By the early 2000s, these programs had borne fruit and the park was sufficiently safe for park managers to take up the ultimate challenge: reintroducing black rhinos in one of the largest operations ever undertaken at that time.

“In 2003, conservation agencies were skeptical about donating rhinos to us, because Zambia was seen as one of the countries where a lot of poachers originated. Eventually, South Africa was willing to take the risk,” says Hugo van der Westhuizen, then-manager of the NLCP. Despite their own at-risk populations, South African National Parks donated 25 rhinos as an acknowledgment of Zambia’s important role in liberating South Africa from apartheid — the first country to donate animals on that scale in Africa.

But raising the money to airlift the donated animals and finding a big enough space with robust protection to keep the rhinos alive proved challenging, leading to hiccups the park would aim to prevent in future operations. The first rhinos were delivered in 2003, but it took another seven years to complete all the translocations. Black rhinos, despite their cantankerous reputation, are very social and form strong bonds with each other and their neighbors, so mixing new arrivals with recently established individuals disrupted their connections and delayed initial mating. “If we could do it over again, with money as no object, it would be better to bring all the rhinos in one go. This would help them settle and start breeding more quickly,” says Claire Lewis, project manager since 2007, who manages NLCP with her husband Ed Sayer.

When the rhinos arrived at the park, local chiefs performed a traditional christening ceremony in front of locals to give each one a name. For many, it was the first time they had seen one of the great animals alive. The rhinos were initially put into large stables to acclimatize to their new environment. After that, they were released into a specially protected area with a unique permeable fence that restricted rhinos to a secured area, while allowing most other animals to crawl underneath it or cross it. This concept has since been used in other national parks, such as in Gonarezhou National Park in Zimbabwe.

Today, the current population shows one of the fastest growth rates on the continent. On the advisement of the IUCN African Rhino Specialist Group, specific numbers are not officially disclosed for security reasons, but the population has more than doubled, making it one of continental significance. “Even though wildlife crime has been ever-present in Zambia, no rhino has been poached since their introduction in 2003. The good population growth rate together with the lack of poaching to date is what makes the reintroduction such a success,” says Richard Emslie, Member of the IUCN group.

Nowadays, most national parks in Zambia are run as a CMP in one form or another. This model of equal partnership has expanded to Mozambique, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Congo and Ethiopia and leads to more effective conservation efforts because governments share the burden with conservation organizations.

But the real lynchpin is local community support. “In the first years of the reintroduction, many people were skeptical about the program, as they mostly saw law enforcement and restrictions,” says Bwalya who became a wildlife police officer in 2007.

Today, attitudes have changed. “The coming of black rhinos created a lot of jobs in our areas. I’m sure very few people can think it would be better without the park. Most people have now seen the value of animals,” says Shadrik Eliko, chairperson of the Community Resources Board for Mukungule, one of four Game Management Areas. The NLCP is now the biggest employer in the region, itself a poaching prevention program: much of the illegal poaching in the past was the result of hunting for bushmeat to supplement diets and incomes.

Besides jobs, the NLCP has also built schools, helped people protect property and fields that are under threat from wildlife, supported women-led micro-finance community conservation banks, trained local people to become bee-keepers and helped establish tourism campsites that are owned and run by local communities.

According to Gilbert Mwale, NLCP Community Outreach Manager, “Most national parks in Zambia don’t have so many programs and so much support from the locals. They bring programs to the communities and communities have to follow, whereas in North Luangwa, we ask people what they need and develop the initiatives with them.”

North Luangwa National Park is also now home to Zambia’s largest, fastest-growing and densest population of elephants. When Claire Lewis and Ed Sayer came to the park in 2007, they only saw elephants down the Luangwa river; now, it’s impossible to move in the park without seeing one.

These developments demonstrate the cyclical nature of successful conservation work: North Luangwa is the only park in Zambia that has rhinos. With a proven robust rhino population, it is easier to get funding from donors to invest in community initiatives and the conservation of other species. To make sure that rhinos thrive and the park retains its status, Bwalya and his colleagues must keep on with their work patrolling the park and surrounding areas on a regular basis. And so on.

As the sun sets behind the horizon, they are settling down for the night ahead. Another gruelling day is over, with a few more still to come. But even though their work is difficult, it is fulfilling, too. The rhino population is thriving so much that plans are underway to create a new founder population of black rhinos in Nsumbu National Park — another Frankfurt Zoological partnership in Zambia.

“My job is not easy,” Bwalya says. “It needs self-sacrifice. Risking is a must and without that, you can’t do it. But we are after conservation and our families know it.“