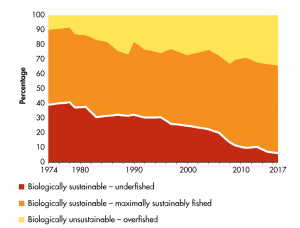

Wait, really? I was under the impression that fish populations are dwindling and the oceans are being overfished like crazy. Is there actually some good news?

Answer: Yes, there is. Not everywhere — in some places it’s true that overfishing is rampant. But I was surprised to learn that in others, including the U.S., the effort to fight overfishing has been extremely successful.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 43 fish stocks have been rebuilt since the year 2000. Now, 84 percent of stocks are no longer overfished. And as we at RTBC have seen, a solution in one country or region can often be replicated in another. Step by step. Success breeds success.

Who owns the fish?

Curious about these success stories, I geeked out on fishing regulations and their impact. Believe it or not there’s a podcast called “On The Line” produced by the NOAA’s office of communications. All hail the deep state!

In a 2014 episode of that podcast, Rich Press (formerly of the office of communications — perfect name for the job!) interviews Sam Rauch, the deputy assistant administrator for regulatory programs at NOAA Fisheries. So there might be a bit of interdepartmental back slapping going on here, but let’s see.

Sam says that in U.S. waters since 2010, “overfishing has essentially ended.” I have to admit, I was kind of stunned to hear this. But according to NOAA data, it’s true: by 2017, 85 percent of U.S. fish stocks were no longer overfished — the highest number since record keeping began. And active overfishing had been eliminated in 91 percent of stocks.

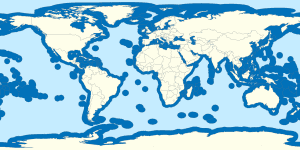

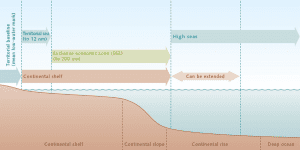

Centuries ago, territorial waters were defined by how far one could shoot a cannon: three nautical miles. (The Scandinavians, who had better cannons, insisted that they should get four.) Over the years, squabbles and even wars broke out as different countries began to claim incrementally more. Eventually, a UN decree enacted in 1982 determined that territorial waters would surround each country by no more than 12 nautical miles — inside that zone, you’re essentially IN that country.

Who gets to fish in these waters is a little more complicated. Gerald Ford signed a law in 1976 giving American fishing boats exclusive rights to fish up to 200 miles off the U.S. coast. This means that, for example, Chinese or Japanese trawlers can’t work in that zone. This area, managed by the NOAA, covers 3.4 million square nautical miles — bigger than the U.S. itself!

Countries sometimes come into conflict over these fishing zones. In 1958, Iceland unilaterally expanded its territorial waters, but Britain refused to acknowledge them. The Royal Navy was sent in to protect British fishing boats, and the Icelandic Coast Guard began cutting the British nets. This became known as the Cod Wars.

Legislation and regulation

The U.S. fishing zone wasn’t always well managed. Ford’s 1976 law was ostensibly meant to block foreign ships from overfishing in U.S. waters, but American fisherfolk continued to overfish there themselves, and the foreign boats simply overfished further out. Another attempt to regulate fishing was passed in 1996 to more clearly define what is sustainable. That law set a 10 year deadline for fish stocks to bounce back. For the most part, they didn’t. So yet another law passed in 2006 set limits on catches — and penalties for exceeding them.

This was more successful. Now, the NOAA carefully monitors catch levels, and if a particular stock does become overfished, it requires a rebuilding plan that will reduce fishing of that species until it has recovered.

This can be hard on American fishers, since many foreign boats sell their fish in the U.S. at lower prices. They also engage in the kind of dredging and trawling that can make for a large catch but also harm fishing grounds. The UN says that globally in 2018, 33 percent of fish were overfished. Global trends are not good.

This is serious. Change has to start somewhere. And it has: As a result of recent laws, the U.S., along with countries like Iceland and New Zealand, now has some of the most sustainably managed fisheries in the world.

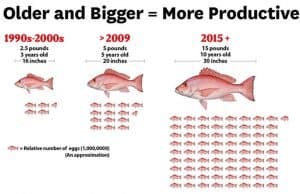

As it turns out, a more sustainable industry is also a more profitable one. We at RTBC have seen this over and over: protecting the environment doesn’t have to lead to economic hardship. When overfishing is successfully regulated, fish stocks rebound and fishing industry revenue goes up.

For example, according to the Environmental Defense Fund, revenues for Gulf of Mexico fishers increased by 100% after catch limits were implemented to rebuild fish stocks. “We’re catching bigger fish and getting more bang for our buck,” Gulf fisherman Buddy Guindon told the EDF.

2020 was a rough year — in many places fish sales and revenues were down. But according to Shannon Carroll, deputy director of the Alaska Marine Conservation Council, “Americans collectively enjoy the lowest number of overfished stocks in our history, and landings revenue is up 18 percent since 2005.”

According to Sam Rauch, it’s not enough to radically restrict fishing and then, after stocks rebound, overfish again. He claims that cutting back a bit can allow fish to return while the fisherfolk keep working. Some fish rebound quickly; others take a little longer. We can still eat our seafood, just not too much. Under this model, “sustainable” means just what the word says: the fish and the industry will be sustained for future generations.

Self regulation

There’s a nuanced management technique that some areas have found to be successful. It’s called catch shares.

Here’s how it works. First, scientists determine how many fish can be caught without causing the population to spiral down. (Counting fish? How do you do that? As it turns out, there are all sorts of ways.) Then, that number of fish is divided among the fisherfolk. So they all have a stake, a kind of ownership, and therefore an interest in keeping the population intact and healthy. This incentivizes everyone involved to manage the asset without forcing them to adhere to top-down regulations or penalties.

Under this system, each fisher’s share is an asset and equity. They can even pass it on to their kids, giving them a direct incentive not to deplete the supply. As fish stocks rise, everyone’s shares are adjusted upwards, which results in them catching more fish and reaping greater profits. Overfishing, as a result, has dropped 60 percent in U.S. waters since 2000. (I admit it’s hard for me to believe, but this comes from the Environmental Defense Fund, not an industry mouthpiece). According to the NOAA, even as fish stocks have been rebuilt, recreational and commercial fisheries provided over $200 billion and 1.7 million jobs to the economy.

Catch sharing has been implemented successfully in many places. In the 1990s, red snapper were being depleted in the Gulf of Mexico. When regulators tried limiting the fishing season, fisherfolk raced to catch as many fish as possible. As a result, fish stocks continued to decline. When they switched to a catch share system, however, in which catch limits were adjusted up or down depending on the number of fish, it became in the fisherfolks’ interest to fish sustainably.

It worked. By 2013 red snapper was taken off the “avoid” list for consumers, stocks began to rebound, fishing costs went down and prices went up. Even the fish got bigger!

What are the challenges?

There are a few big ones. Overfishing is a major problem in many countries, and often those fish are shipped back to the U.S. where they compete with local, sustainably caught fish. Severe quotas that change year by year can make it hard for fishers to know what their annual income might be, making it harder for them to plan their lives or get loans based on projected income. Finally, getting accurate data on fish counts costs money and remains an imperfect science — the management of fisheries can’t work without the data.

One has to start somewhere

It would be easy to get complacent with all this surprising good news about sustainable fishing in U.S. waters, but globally the picture is not so bright. Overfishing in some areas is still rampant, and destructive practices like trawling and dredging continue. This is the tragedy of the commons when the commons encompasses much of the world’s oceans. But sustainable fishing has proven to be economically beneficial — as stocks recover in regulated areas there are more jobs in the fishing industry, and more fish, meaning more income, for both the present and the future. Here’s hoping common sense will triumph over rapacious short-term thinking.