With an ear-deafening bang, Jason Barnes’ world exploded in January, 2012. “I saw a pink flash and thought a bomb went off,” he says about that life-altering moment. The then-22-year-old was cleaning the exhaust duct at a restaurant near Atlanta when a transformer defaulted and sent 22,000 volts through the right side of his body, a load that could have killed him.

“I was standing with rubber boots in water, so I was not grounded,” he remembers. “I got completely cooked.” He survived, but after the seventh surgery the doctors concluded that his right hand could not be saved, and amputated it below the elbow.

Before the accident, the lanky blond musician with the tattooed arms and the black plug earrings had played the piano, the guitar and the drums. “The drums were the most important thing in my life,” he says. Now his dream of pursuing a professional career as a drummer seemed to be over. For several months, he became so depressed he barely got up from his bed.

“My world collapsed.” He tried to find the upside: “Most people who take such a massive hit lose all four limbs. I was lucky to only lose one hand.” Three months after the accident, he dragged his drum kit out of the garage, fastened a stick to his bandages and played, “out of pure boredom and despair.” But it hurt like hell, and he didn’t have enough grip.

Weighed down by negative news?

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.His drum teacher introduced him to Gil Weinberg, the founding director of the Georgia Tech Center for Music Technology and an eminent authority on artificial intelligence. The Israeli-born computer scientist had ambitions of becoming a concert pianist, but while he studied in Tel Aviv and then at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), he became fascinated with artificial intelligence.

Combining his two passions, he has created experimental “robot musicians” such as the marimba-playing Shimon who writes his own lyrics and has his own Spotify account. With artificial intelligence, Shimon plays and improvises with human bandmates. When listeners close their eyes, they usually think it’s real people jamming.

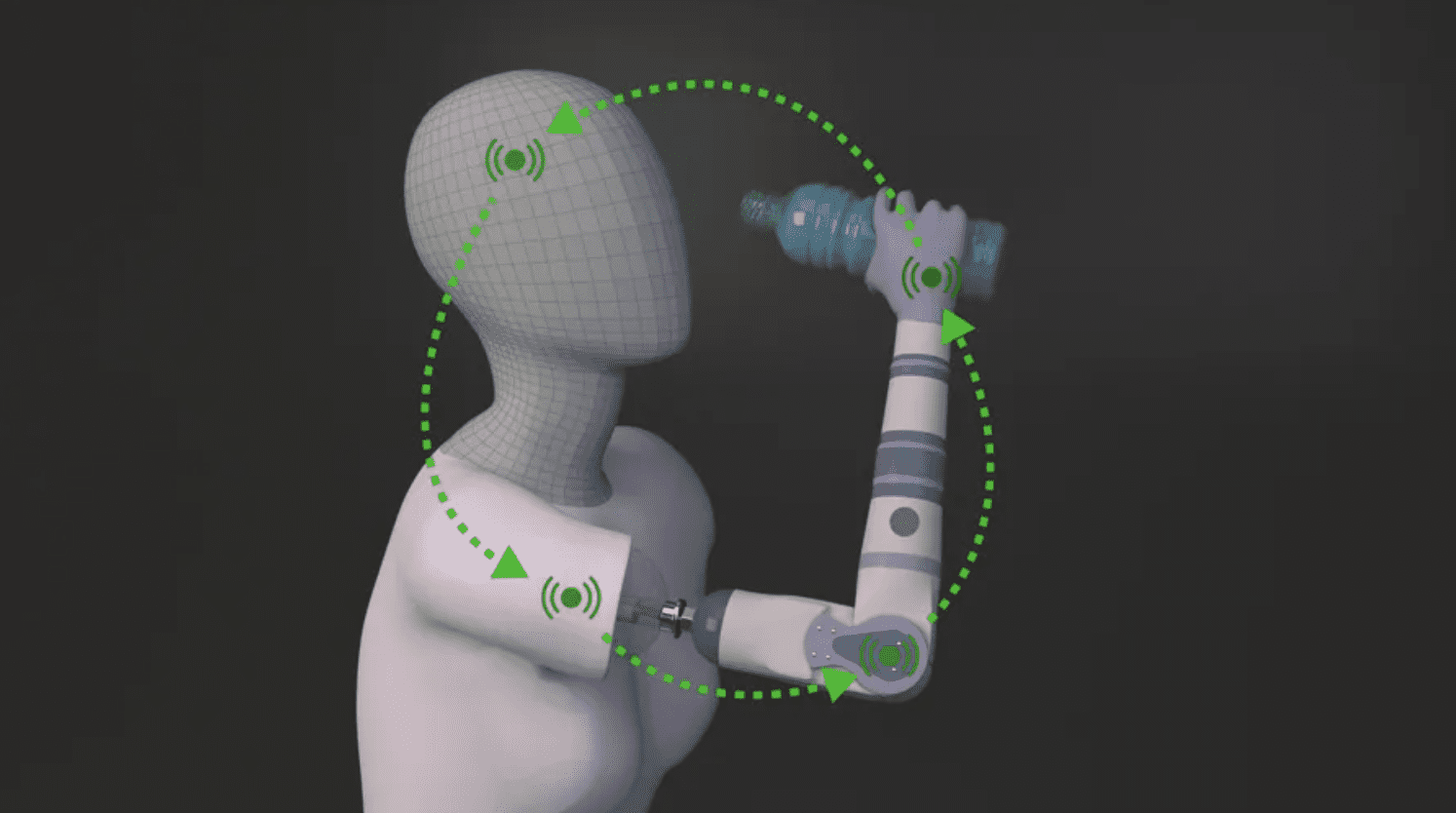

Over the course of several months, Weinberg combined his musical talents with his A.I. skills and developed bionic prosthetics tailor-made for Barnes to play the drums. “We use electromyography (EMG),” Barnes explains. “Its sensors on my upper arm muscles pick up signals from my residual limb. I can flex my muscles to tighten my grip, and when I relax my muscles, it loosens the grip.”

The bionic arm includes two drumsticks — one that translates Barnes’s muscle movements and a second, autonomous stick that has been “trained” by machine learning. After being fed many hours of improvisations of jazz greats such as John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk, the A.I. drumstick can improvise on its own. “It’s almost like having a second, bionic drummer in the band,” Barnes half-jokes. With his A.I. arm, Barnes even made it into the Guinness Book of World Records as the world’s fastest drummer, achieving 20 hits per second with each stick.

“That was cool,” he said, but what matters more to him is how the technology has transformed his entire career, benefits him every day in his life and has the potential to benefit others. The “cyborg drummer,” as some media outlets nicknamed him, is now living his dream as a full-time producer and songwriter, and has performed internationally under his stage name Cybrnetx, including at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC. Via Zoom, he proudly shows off his brand new recording studio near Atlanta, which he built himself.

With a quick flip from his left hand, he rotates his artificial right hand out of its metal socket and demonstrates how he can exchange his “everyday hand” with a “music hand.” “It just honestly works insanely well,” he says about the various prosthetic hands that allow him not only to play music but also to tinker with his car and regulate his sound mixers. “The only thing I can’t do is clip my fingernails,” he quips.

It is hard to imagine how different Barnes’ life would have evolved, had he not made the connection with Gil Weinberg. Barnes is the beneficiary of high-end research that might one day ease challenges not only amputees face in accomplishing very precise tasks. “People are always afraid robots will take away our jobs,” Weinberg says. “Here, we have a human who wouldn’t be able to work in his job without robotics.”

Weinberg is convinced that the astonishing progress in bionics opens enormous possibilities for other clients, for instance, people who have suffered traumatic brain injuries and need to relearn movements. A different team at Georgia Tech has invented a glove that teaches people to play the piano or learn Braille within a few hours (it usually takes several months) using haptic passive learning. “You need incredible precision and dexterity to make music,” says Weinberg, “so when we make it possible for them to play the piano, they can do pretty much everything else such as typing on a keyboard or doing mechanical work.”

To this end, his team has also created a black arm called the “Skywalker” with which Barnes can control each finger separately to play the piano. Star Wars hero Luke Skywalker famously lost his right hand in a struggle with Darth Vader and replaced it with a prosthetic that let him grip and feel. Ultrasound sensors translate the muscle tension in Barnes’ upper arm into subtle signals and finger movements. It might not be enough for Carnegie Hall, but he can play the title score of Star Wars and Beethoven’s Ode to Joy.

“Identifying where we can create something unique, where robots inspire and push us to uncharted territories is tricky,” Weinberg says, “because we don’t want people to think we are replacing musicians.” He is fascinated by exploring new forms of creative expression through the interaction between human artists and robots. In his latest production, FOREST, he “trained” robots and humans to “trust” each other and dance together, emulating and responding to each others’ movements.

“It’s like having these band members who are not quite opening up to you yet, but they’re good musicians,” Barnes describes the experience. “We kind of vibe together.”

With the help of A.I., machines can already paint like Rembrandt, write entire articles, or improvise like John Coltrane. At the same time, blind people can learn to see with bionic eyes and amputees can run and jump on cyborg legs. The next frontier in sophisticated prosthetics is achieved through brain implants. At the University of Pittsburgh, researchers tacked rice-sized electrode arrays into the cortex of a partly paralyzed young man, allowing him to control his paralyzed hand with motion commands and touch feedback.

Atom Limbs, a new startup, is trying to bring mind-controlled prosthetics to the market by 2023 with a technology developed at Johns Hopkins’ Applied Physics Laboratory with a $120 million grant from the Defense Department. 200 sensors give very precise, detailed sensory feedback. (For comparison, Barnes’ current prosthetic has eight sensors.) Gil Weinberg does not want to go as far as implanting brain chips, but Barnes is not afraid to experiment and is eagerly trying to get on Atom Limb’s waitlist.

Because high-tech prosthetics are unaffordable for most people, other inventors are trying to make simpler versions available through Open Source technology. French inventor Nicolas Huchet who lost his right hand in a work accident, developed his own smart prosthetics and is now leading the nonprofit My Human Kit that prints prosthetics for less than $1,000 through Open Source technology and 3D-printers.

The cost is the biggest disadvantage of Barnes‘ superhuman drumming hand, too: Because it is owned by Georgia Tech and cost more than $100,000, the insurance company does not allow him to take it home or play with it outside of Georgia Tech projects. Therefore, Barnes has transitioned to much simpler 3D-printed models for his other music projects and as his “everyday hand.”

After an attempt to fundraise for him on Kickstarter failed, Google and Georgia Tech collaborated on building him his newest “music hand” with TensorFlow that he can take home. “It uses artificial intelligence, but does not play anything on its own,” Barnes explains. “It’s able to read my muscles and determine what I’m trying to do.”

He and the team are still working to improve it, making it sleeker and lighter, hopefully in time for Barnes to play at the opening of the Invictus Games in The Hague this year. “In the ’90s, this stuff was science-fiction,“ Barnes marvels. “When you look at the first Star Wars movies, they seemed incredible. Now it’s happening.“

Barnes is fascinated by the possibilities of body hacking. He already has an NFC implant, a chip under the skin above his left thumb, with which he can open his studio door and make online payments. Barnes believes that in the future, “everyone will be a bit of a cyborg. Those movies inspired people to dream up this kind of technology and make it a reality. My ultimate goal was always to play music and go places. This is all I ever wanted in the first place. It’s all coming to fruition.”

May the Force be with him.