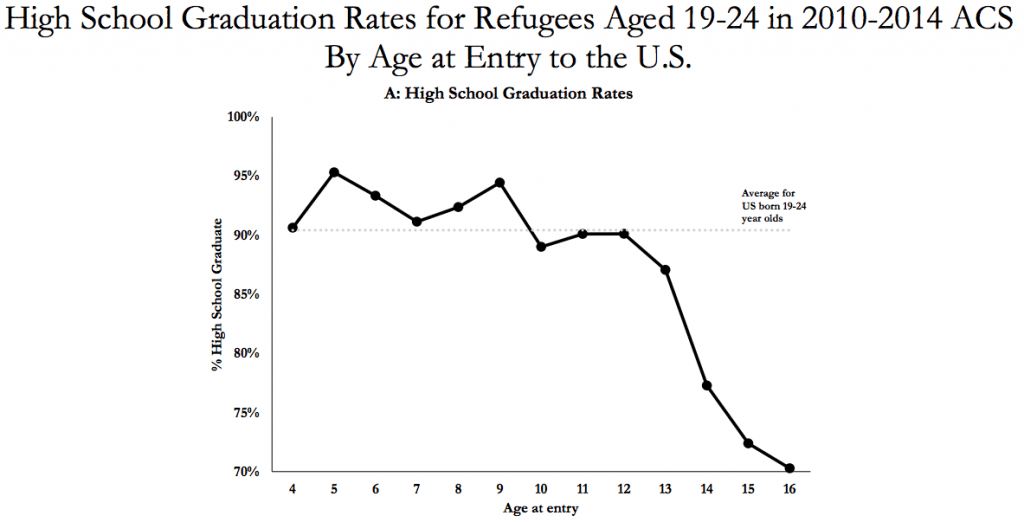

If refugees arrive in the United States at a young age, under 13, they are almost as likely to graduate high school as their U.S.-born classmates. If they arrive after the age of 14, however, their likelihood of graduating plummets.

In Atlanta, Georgia and Columbus, Ohio, there is a pair of schools changing that, raising the graduation levels of their refugee students to a level equal to or even exceeding other American students. The two campuses are part of an ambitious educational project called the Fugees Academy. Their starting point? Soccer.

The Fugees Family, as it’s known today, began as a soccer team. In 2004, Luma Mufleh, originally from Jordan, started a team after playing soccer one day in the street with a group of refugee boys from war-torn countries: Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, Bosnia, Burma, Somalia, Sudan. Soon, the soccer team expanded to include tutoring, a summer camp and eventually a small school. The all-refugee school grew, gaining official status with the Southern Association of Independent Schools as Fugees Academy.

The reasons that refugee students struggle in American schools are many, ranging from language barriers to home dynamics—the older they are, the more likely they are to have arrived in America alone without parents, or at least without a mother, studies show. But according to Mufleh, there is another problem: refugee children are put into the school grade appropriate for their age, not their academic level. Fugees’ website describes the conundrum as such:

The Fugees Academy has a unique goal, to educate refugee children in an environment that understands their unique challenges. These children are left behind in a traditional public school system. They come to the United States after being forced to flee their home countries. Most have lived through traumatic experiences and have spent time in refugee camps, where education is neither a priority nor an option.

Once settled in the U.S., these children are behind their peers, both academically and socio-economically. Many have never had any formal schooling, and their parents are often unable to read or write in their native language or English. Lacking the support and guidance they need to succeed in traditional public schools, these refugee children drop out of school and never learn English, develop fundamental academic skills, or identify themselves as a valuable part of American society.

The Fugees Academy attends to the needs of these children, who, at 14 might read at a kindergarten level, if at all. It offers children a bridge from isolation to socialization and learning. The school strives to give its students the support, guidance and direct instruction necessary to put them on a path to better adjustment, high school graduation and further successes. Our programming has demonstrated that in a highly structured environment where rules and expectations are clear, and creativity and individuality are nurtured, refugee children don’t just catch up—they become stellar performers who can meet rigorous academic standards.

While daily soccer programs are still at Fugees’ core, academic achievement has flourished. On the Iowa Test of Basic Skills, the Fugees students compare favorably or better with all students attending the area’s two public middle schools. The Fugees Academy graduated its first class in 2016. With a 90 percent graduation rate, 100 percent of their graduates have gone on to attend college.

It’s a success so great that Mufleh was named a Top 10 CNN Hero in 2016; she received the Richard Cornuelle Award for Social Entrepreneurship from the Manhattan Institute and Inc. Magazine named her TED Talk among the most inspiring of 2017, alongside talks by Elon Musk and Tim Ferriss.

Fugees Academy is expanding, with more campuses set to come (next up, Cleveland), and now provides consulting services to other institutions that provide aid to refugees, helping them offer more effective, impactful, culturally appropriate services to refugee and immigrant communities.

This story is part of a collection called Education Against the Odds: Stories of teaching and learning under difficult conditions. Read more here.