This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering K-12 education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

It was the first day of the 2021 fall semester and Ajah Johnson could not believe what her teachers were telling her. By the end of the course, the instructors said, she and her peers would get to choose how to spend $10,000 to upgrade their school however they decided was best.

“I thought it was a lie,” Johnson said, figuring the classroom exercise involved make-believe money. “There’s no way they’re giving us $10,000.”

But to her delight, the cash was real.

Over the following months, she and her peers at Central Falls High School in Rhode Island received lessons in budgeting, survey techniques and local government, then eventually designed proposals for how to allocate the money. It was the first time Johnson, who grew up in Virginia and had moved to Rhode Island the previous year, ever remembers getting a say in how her school was run.

“I feel like I got to make an impact,” she said. “We felt like we were valued.”

The then-high school junior didn’t know it, but her efforts were feeding into a wider movement revolutionizing democratic engagement far beyond her campus.

The elective, first offered in 2019, has served as proof-of-concept in Central Falls for a process called participatory budgeting, which gives stakeholders a direct say in how public funds are spent. Since then, the model has spread throughout the city and is beginning to take hold statewide.

“[The class] has triggered a lot,” said City Council President Jessica Vega, who helped launch the elective.

Weighed down by negative news?

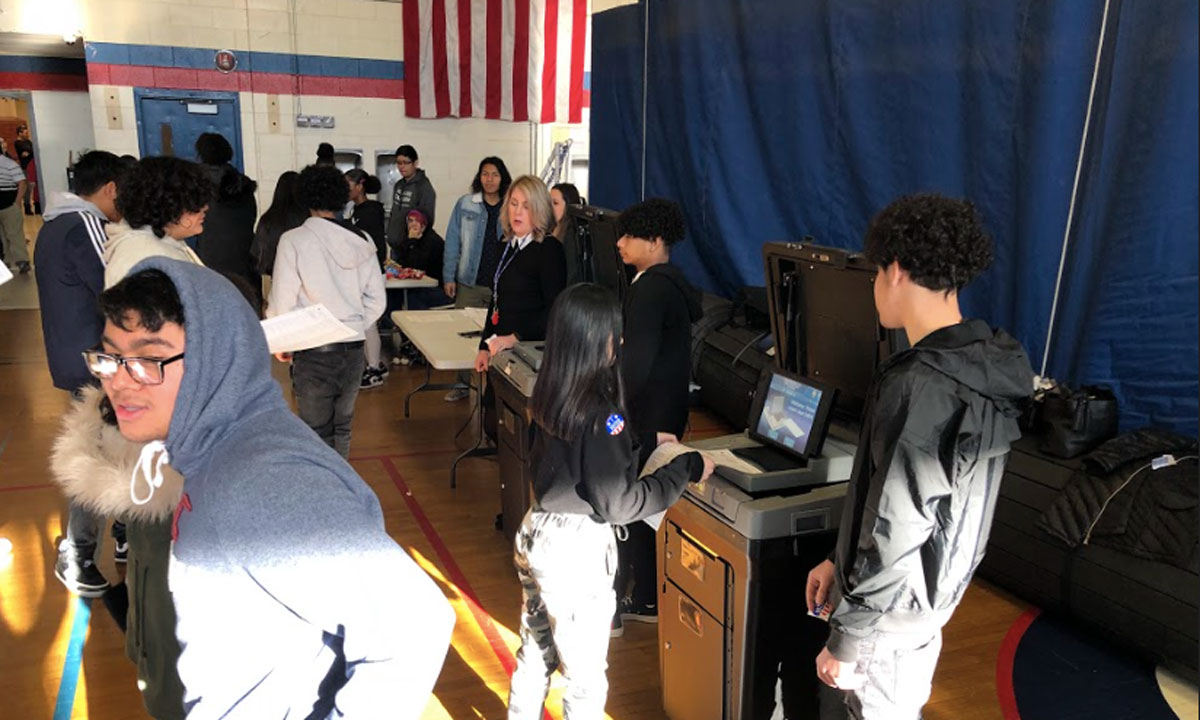

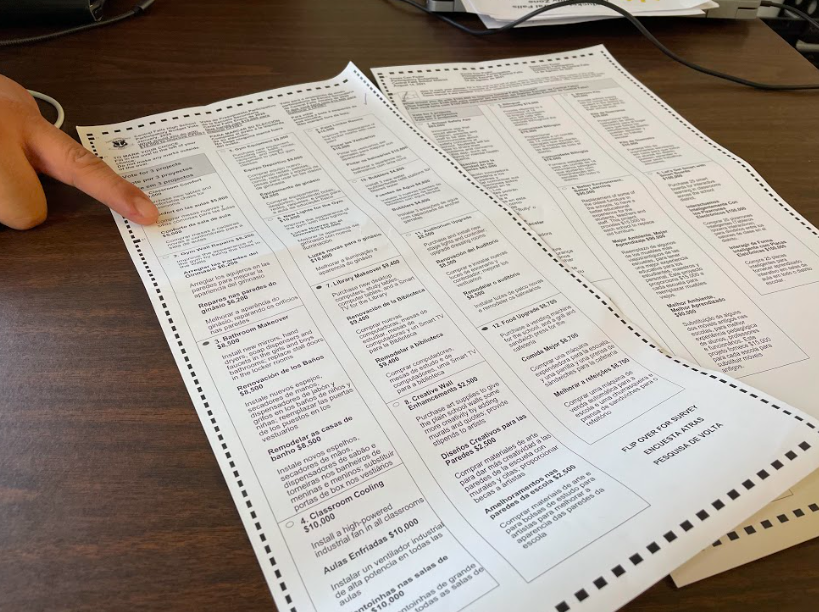

Our smart, bright, weekly newsletter is the uplift you’ve been looking for.She made sure local officials knew how successful the course was, inviting them to the school’s voting day at the end of the semester. Thanks to a partnership with the Secretary of State’s office, students selected a winning project — new bathroom mirrors to replace ones a teacher said resembled “tin foil” — by casting customized ballots using official voting machines.

“Folks in power in that room came in and saw that. It helped them say, ‘OK, this does work.’ So we were able to expand and start thinking about what a citywide process looks like,” the council president said.

In 2020, when the school district received federal COVID relief dollars, the superintendent earmarked $100,000 for community members to allocate using the same method of direct democracy. After a months-long process, voters decided to invest the full sum into boosting the district’s afterschool learning programs.

Then again in 2021, the City Council set aside $50,000 for elderly and disabled people to choose how to make accessibility upgrades.

Now, the Rhode Island Department of Health is using a similar tactic in Central Falls and two nearby cities, Providence and Pawtucket, allowing the communities to decide by vote how to spend a collective total of nearly $1.4 million to reduce health care disparities.

“The local success of participatory budgeting in Central Falls was a very encouraging example,” Department of Health spokesperson Annemarie Beardsworth wrote in an email.

Patricia Martinez, the school district’s chief equity officer, marvels at the swift progress.

“It’s really taken on a life of its own,” she said. “It’s a new wave of democracy, especially for underserved BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of color) communities.”

Hearing student voices

Over two-thirds of Central Falls’s 22,500 residents are Latino and 35 percent were born in another country. Some 45 percent of students in the district are classified as multilingual learners. At roughly one square mile in area, it’s Rhode Island’s smallest and most densely populated city. By measures of income, it’s the most impoverished metro area in the state.

However, by the less tangible measure of social cohesion, there’s an unmistakable richness to the community. Even on brisk days, neighbors lean over porch railings to chat with passersby; the receptionist in the district office calls the person on the other line “darling.”

As students began brainstorming their projects and speaking to adults in the school about the issues they thought needed fixing — shabby gym equipment or lackluster cafeteria options, for example — a miraculous thing happened, Jennings and her co-teacher Emmanuel Ramos observed.

“As soon as students started making noise about things they wanted to see fixed, things started to get fixed,” Ramos said. Adults in the building heard what students were saying and responded.

Fresh new basketballs appeared in the gym, a salad bar popped up at lunch and the office supply company W.B. Mason offered to donate new furniture for the library, he said.

That’s actually a design feature of the model, explained Brown University education professor Jonathan Collins, who studies direct democracy in schools.

“The interesting thing about participatory budgeting is that the deeper you get into it, the more you quickly realize, it is not about the money,” he said. “[The process] is a tool that can really create and strengthen your civic infrastructure.”

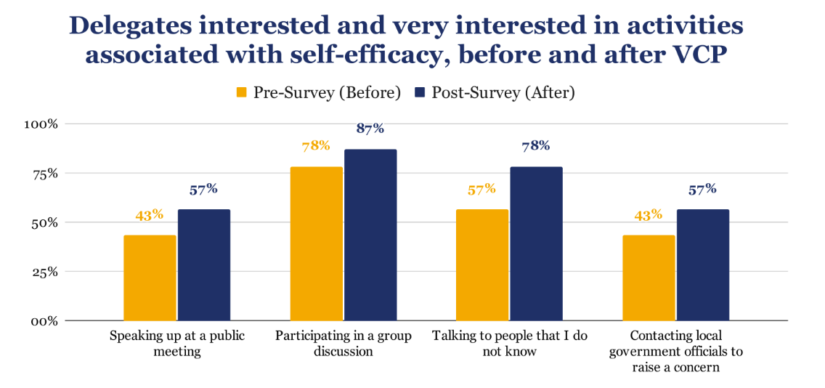

Collins led an evaluation of the district’s decision to let community members allocate the $100,000 in COVID relief funding. After that deliberation, the predominantly low-income Latino participants reported double-digit increases in their likelihood to voice concerns to a local official, he found.

The results back up his prior research, which showed that when school districts create meaningful opportunities for parents to make their voices heard, they’re more likely to speak up about issues related to their children’s education.

For students more broadly, when they perceive their perspectives to be heard and reflected in school policy decisions, it can have a positive impact on academic outcomes like grades and attendance, according to a March 2022 study published by researchers at the University of California, Riverside and Northwestern University.

Central Falls Principal Robert McCarthy recognized the participatory budgeting elective course as an opportunity to, quite literally, put his money where his mouth was on empowering students.

“Always kids are like, ‘You say that we have a voice, but what does that really mean?’” he said. “When you’re putting $10,000 behind something … it definitely speaks to this notion of, you have some power, but with power comes responsibility.”

‘My class did this’

The participatory budgeting model first launched in 1989 in Porto Alegre, Brazil. It quickly spread to over 100 cities in the country, helping reduce child mortality by roughly 20 percent in those metropolitan areas. Several US cities including Chicago, Seattle and New York have since employed the process and schools in San Jose, California, Phoenix, Arizona and Brooklyn, New York have brought the idea directly to students.

Only Central Falls, however, has ever made the process into a full-blown course offered within the school day, believes Jennings, who formerly worked for the Participatory Budgeting Project, a nonprofit organization that works to expand the model in the US and Canada.

Other school districts that have used participatory budgeting typically hold sessions after school, which can exclude students who have evening jobs, athletics or child care responsibilities, she points out. As a semester-long, credit-bearing elective, the Central Falls class, on the other hand, has reflected the diversity of the school’s student body.

“It’s been a very wide mix of students, including students from all different grades, too,” Jennings said. “The class is for everyone. Students of every ability, we can find a niche for them.”

On the first day, students try out a mini-version of their larger mission, collectively choosing how to use $50 to spruce up their classroom. Then, over the ensuing weeks, they receive training in budgeting tactics, survey techniques and then finally, develop project proposals. The class culminates in a school-wide vote to select a winning idea from among a dozen total proposals.

Though the Omicron wave forced last year’s election online, the last live vote in the 2019-20 school year brought more than three-quarters of the roughly 800-person student body to the gym to cast ballots, Jennings said. This year’s live vote will take place in the spring.

Johnson, who took the course last year, said the experience was “once in a lifetime” and taught her several lessons she didn’t expect, like financial planning and what it takes to turn an idea into a reality.

“I learned so many different things about loans and investments,” she said. “A lot of the things that I learned in that class were brand new.”

Her group’s project sought to improve furniture in the library where previously, students would sit on the floor because the chairs were so uncomfortable, she said. Though her proposal came in second, $3,000 was left over from the winning project — a facelift for the cafeteria. That sum coupled with the W.B. Mason donation has revamped the library considerably, in her estimation.

Seeing the changes, the high school senior relishes the new sense of ownership she feels over her campus. Students linger in the library now, which they never used to do, she said, and the cafeteria has a new monitor to display the lunch options.

“I see it everyday. When I walk in the lunchroom, like, ‘Oh, my class did this.’ When I walk in [the library], I’m like, ‘My class did this.’ I see it every single day.”

Implementing the model

Though there’s now momentum behind the elective course in Central Falls, Jennings recognizes that getting participatory budgeting off the ground can be a difficult task.

“The hardest part is finding the pot of money,” she said.

In 2019-20, the school district agreed to dedicate $5,000, with the other half coming from a private donor. In 2021-22, after losing a year to the pandemic, the full $10,000 budget came from outside fundraising, as dozens of community members pitched in. That allowed the district to save cash, which, in addition to COVID stimulus money the superintendent earmarked for the elective, means the course is now funded several years out, said Tatiana Baena, the district’s grant director.

“We’re trying to really sustain the program and make sure that it can be ongoing,” she said.

But even with the funds secured, students who dream of pricey upgrades like a new basketball court or state-of-the-art air conditioning get tough lessons in economics, said Ramos, the co-teacher.

“Ten thousand dollars, ultimately, it’s not that much,” he said.

But over time, the impact will compound, predicts Collins, who is closely following the efforts from nearby Providence.

“With the course, every year, there’s a new group of students who are coming in and gaining these skills and gaining this perspective and leaving with this feeling of empowerment,” observes the Brown University researcher. “In Central Falls in, maybe it’s 10 years, maybe it’s 20 years, if they keep doing this, you’re going to look up and you’re going to realize like, ‘Oh, wait, they’ve been able to solve some really, really major problems because they have this whole civic infrastructure.’”

And for some residents, the changes have been more immediate.

Baena, the district’s equity officer who also serves as an elected councilwoman, helped spearhead the city’s recent participatory budgeting effort. The steering committee, she explained, felt it was important that “anyone in the community could have an opinion” and thus decided all residents could cast a ballot, regardless of whether they were registered state voters. One person from voting day in June stands out in her memory.

The woman was elderly and had lived in Central Falls for decades, Baena said, but as an undocumented immigrant, she had never voted in a US election. After filling out the bubble sheet, she held the paper out to the councilwoman.

“You put it in the scanner,” the elderly woman asked Baena.

“No, no, no, señora,” Baena responded. “I want you to know how this feels. You’re going to put it into the scanner.”

The woman fed her ballot, printed by the Secretary of State’s office, into the official voting machine. Smiling, she turned back to her councilwoman.

“Here, my voice matters.”