On October 7, 2020, the sky over the sultry Mexican fishing town of Puerto Morelos began to darken. Hurricane Delta’s winds amassed like a riotous mob and smashed directly into the diminutive Caribbean pueblo.

“Everyone was hiding at home with their families, nervously praying for as little damage as possible,” recalls Jacob Rubio, a local marine biologist and scuba instructor.

They didn’t get their wish. The storm’s 100-mile-per-hour winds claimed several of the town’s structures, including its pier. Less noticeable, but perhaps even more consequential, was the damage sustained by the vibrant coral reef just offshore.

Hidden beyond Puerto’s ivory beaches lies the Mesoamerican Reef, the second largest barrier reef system in the world. Rubio is part of the local brigade of volunteer conservationists who care for it. A week after the hurricane, when the sea had settled, he was among roughly 30 ‘Guardians of the Reef’ who set about clearing debris and re-rooting and re-attaching damaged coral colonies.“We worked 12 hours every day for a month and a half,” says Rubio. “It was exhausting.”

Normally after a natural disaster, when the need for help is widespread and urgent, the rapid restoration of a coral reef might not rank high on the list of priorities. But the Guardians’ work was enabled by a pioneering collaboration aimed at saving the reef and the economy it supports: this 100-mile stretch of the Mesoamerican Reef is the world’s first natural asset protected by an insurance policy. Successfully tested by Hurricane Delta, the policy provides a fast injection of cash for reef repair after a storm. Time is of the essence — without quick restoration, coral colonies can die within a few weeks.

Insuring the Mesoamerican Reef as if it were any other valuable asset represents an innovative approach to leveraging the economic value of nature to pay for its own conservation. The model is the product of a collaboration between the local government, hotel owners, an international NGO and an insurance behemoth — all of whom believe it can be exported to protect not only the world’s reefs, but also other ecosystems such as mangroves, wetlands and forests.

“This model can be scaled up and applied to protect many different natural assets and the eco-services they provide, with insurance payouts enabling fast response and restoration activities,” says Philippe Brahin, head of Americas Public Sector Solutions at insurer Swiss Re. “We are actively trying to replicate the program in other parts of the world where we identified natural assets playing an important part in climate adaptation.”

The Mesoamerican Reef program

The idyllic Riviera Maya on Mexico’s Caribbean coast is the country’s chief tourist attraction, contributing around $10 billion in annual tourism revenues. Spanning 700 miles of that coastline, the Mesoamerican Reef plays a fundamental role in both the local ecosystem and the local economy. But its future, and those that rely on it, are under threat. Since 1980, 80 percent of the reef’s living coral has been lost or degraded by pollution, overfishing and storms.

This isn’t just a loss for snorkelers. A healthy coral reef can reduce up to 97 percent of a wave’s energy before it hits shore, limiting the effects of storm surge and coastline erosion. Unhealthy reefs, however, are themselves vulnerable to storm damage, losing 15 to 55 percent of their coral cover after a strong hurricane, decreasing their protective qualities. In the Riviera Maya, research has shown that a one-meter loss in the height of the reef crest could double the damage to local homes and hotels. To make matters worse, climate change is resulting in more hurricanes: last year, the Atlantic saw the most named storms on record.

Following two catastrophic hurricanes in 2005, causing $8 billion of damage on the Riviera, researchers at non-profit The Nature Conservancy (TNC) wondered why Puerto Morelos had come out relatively unscathed. Subsequent analysis pointed to the protection provided by the town’s healthier reef section. In 2014, TNC researchers put a dollar value on what the absence of the reef would cost the region’s tourist industry, and worked with Swiss Re risk modellers and local stakeholders to devise an insurance package for it.

In 2018, the groups created a trust to purchase the insurance policy and pay for the reef’s ongoing maintenance by the newly established reef brigades. The Coastal Zone Management Trust was funded by the government of Quintana Roo, with taxes paid by hotels for use of the beaches. The following year, the trust took out the first-ever policy on a natural asset from the Mexican insurer Afirme Seguros, with Swiss Re serving as the reinsurer; the policy was renewed by the trust in June 2020 for $220,000.

The insurance is a one-year parametric policy, triggered when wind speeds exceed 100 knots in a predefined area, allowing for swift damage assessments, debris removal and initial repairs. Enter the reef brigades, who are trained to spring into action after a hurricane. If necessary, longer periods of restoration and recovery work may follow to restore the reef’s value as a coastal barrier––in those cases, the volunteers are compensated for their time.

Hurricane Delta was the model’s first test. Following the storm, the policy paid out $850,000 to the trust fund, and over the next three months, the brigades used the money to stabilize 2,152 uprooted coral colonies and re-attached 13,570 coral fragments.

“It was a very significant milestone in our work to explore the use of insurance as a mechanism to protect at-risk coastal ecosystems,” says Mark Way, director of Global Coastal Risk and Resilience for TNC. “The fact that the insurance policy paid out, and funded vital reef repair activities, is a win for nature and a win for the coastal community, and it will drive further interest in conservation finance and the need to protect marine ecosystems across the globe.”

Insuring nature

Across the world, billions of dollars of built capital — from luxury hotels to fishing villages, roads to power lines, shopping centers to beach bars — are protected from flooding by coral reefs. In the U.S. alone, coral reefs provide flood protection to over $1.8 billion of coastal infrastructure and economic activity. And that doesn’t even take into account the appeal that reefs hold for visitors from afar — a recent study by TNC scientists found that coral reef tourism generates $36 billion globally every year.

“What is attractive about this model is that it allows an insurance company to add a practical solution to its client portfolio; and one that recognizes the economic value of nature’s services — that’s really transformational,” says Alejandro Litovsky, founder & CEO of Earth Security, a consultancy aimed at linking global finance to nature’s capital. “It also ensures that local stakeholders are invested in protecting the natural assets on their doorstep.”

Indeed, there’s no reason similar policies couldn’t be used to insure forests, which soak up water and prevent landslides; coastal salt marshes, which absorb storm surges; and peat bogs, which store vast amounts of carbon. One of the biggest opportunities is mangroves, which offer coastal cities a protective shield against extreme weather up to 50 times more cost-effective than a cement wall. In 2017, mangroves prevented $1.5 billion in flood damages in Florida, protecting over half a million people during Hurricane Irma. Damages were 25 percent lower in the Florida counties where mangroves were present.

A recent report identified 3,000 kilometers of coastline in 20 states, territories and countries in the Caribbean region where post-storm mangrove restoration — which could be paid for by insurance — would provide flood-protection benefits that “significantly outweigh” the cost of rehabilitating the forest.

But the idea of insuring natural assets isn’t without its problems. Perhaps most importantly, there’s still a question mark over who is willing to pay for the coverage. “For this model to scale to different areas, we need to figure out what other economic actors are benefitting from this ‘ecological protection service’ and convince them of the role that insurance can play,” says Litovsky. “My experience of working on this in emerging markets is that the demand is not there yet.”

There is also a need for the insurers to properly adopt the protective value of nature in their underwriting models, so it is reflected in the insurance premiums they calculate for coastal clients. For example, an insurer should charge a hotel less for its catastrophe insurance if there’s a healthy mangrove forest on its coastline. “The power of that would be going from an insurance product that works only in the areas that have stakeholders willing to pay for it, to creating an incentive through cheaper insurance for any company to preserve their natural capital,” says Litovsky.

In fact, the Mesoamerican Reef policy was not without problems of its own. It took a few weeks for the government to receive the payout, and then almost another month for the trust to decide how to distribute it. “The insurance payout covered all the necessary work, but the funds just didn’t come fast enough,” says Melina Soto, a logistics volunteer for the Guardians.

First of many

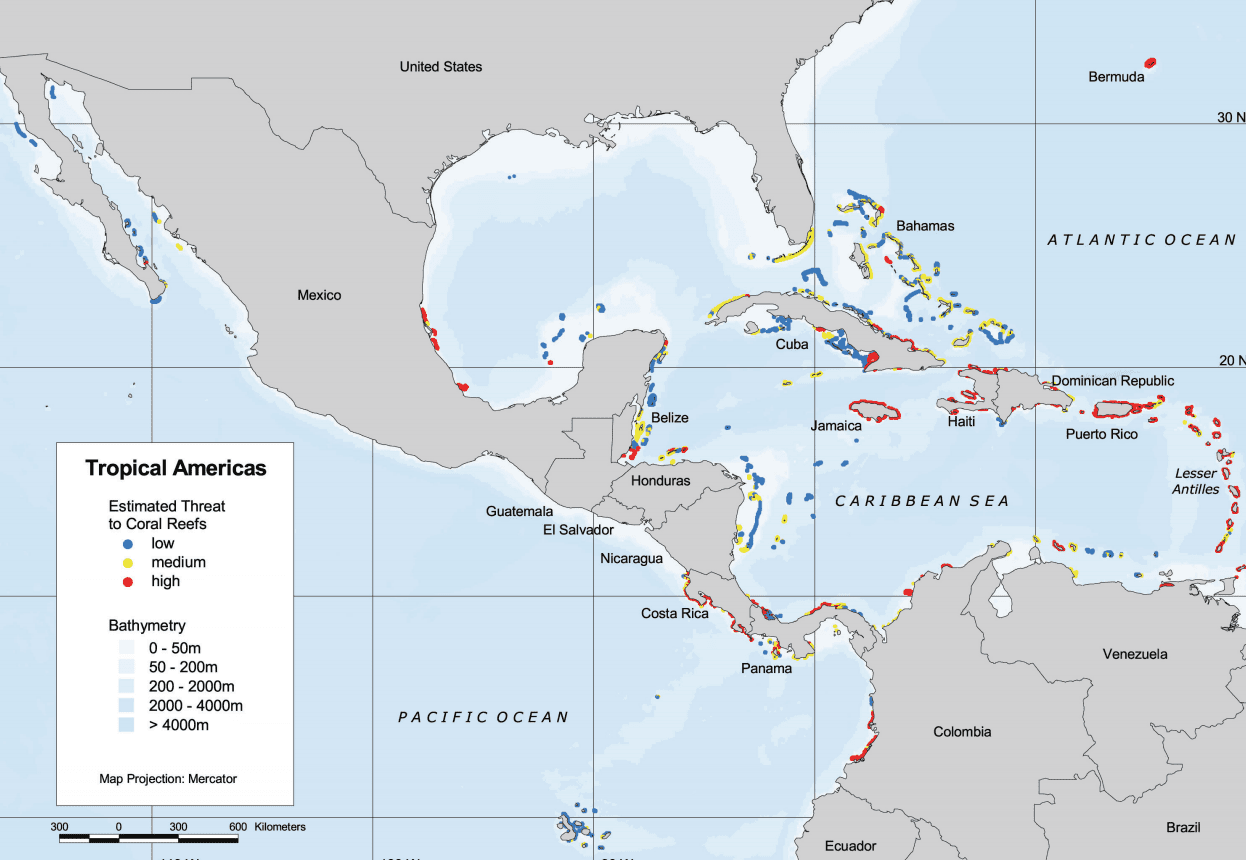

Nonetheless, all the stakeholders were happy with the outcome of the program and, looking ahead, its creators are working to extend the insurance to cover more stretches of the reef, off southern Mexico and Central America. With funding from Swiss Re’s philanthropic arm, TNC will train reef first-responder brigades in Belize, Guatemala and Honduras. They are also collaborating with the UN Development Program and the insurance industry to export the model to protect coral reefs and other ecosystems in the Caribbean, Asia, Oceania, the U.S. and South America.

TNC is embarking on feasibility studies for reefs in Hawaii, Florida, Indonesia, the Philippines, the Sullivan Islands and Fiji. And, along with Swiss Re, the NGO is aiming to create a policy for Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, and exploring policies for mangrove forests in Mexico, Brazil, China and Southeast Asia.

Going forward, insurance could play an increasingly important role in facilitating investment into such nature-based climate solutions, creating more resilient ecosystems and communities as a result — something to which the residents of Puerto Morelos can now attest.

“The community here realizes how important the reef is for fishing and tourism, and are fully behind this program,” says volunteer Arcelia Romero Nava, nodding toward the boats stationed out on the reef. “We get new volunteers every day, and all up this coast, towns are setting up their own brigades. Something big has started here.”