This story was originally published in the Daily Yonder.

Adaline Sneak lives at the end of a long, unmarked dirt road in a rural area of the Navajo Nation in Utah. Getting there requires a high clearance vehicle and at least moderate navigation skills.

Residents here don’t have typical addresses with street names and house numbers. Until recently, Sneak’s official address was even vaguer than the directions a gas station clerk might give a lost driver — seven miles south of Montezuma Creek, Utah, County Road 410.

She can’t get mail with an address like that, nor could someone search directions to her house on Google Maps, for example.

But for someone like Sneak, an address like this is more than just inconvenient. It’s life-threatening. Sneak suffers from seizures, and about a year ago, an ambulance got lost on the way to her house because of her ambiguous address.

“We almost lost her that day,” said Arlene Begay, Sneak’s mother. The ambulance eventually made it to Sneak’s house, but only because someone on the emergency response team happened to know Begay’s sister, whom they called for directions to Sneak’s house.

“That’s happened a few times actually,” Begay continued, recalling other times the ambulance had gotten lost. But now, any confusion over Sneak’s address is hopefully cleared up for good.

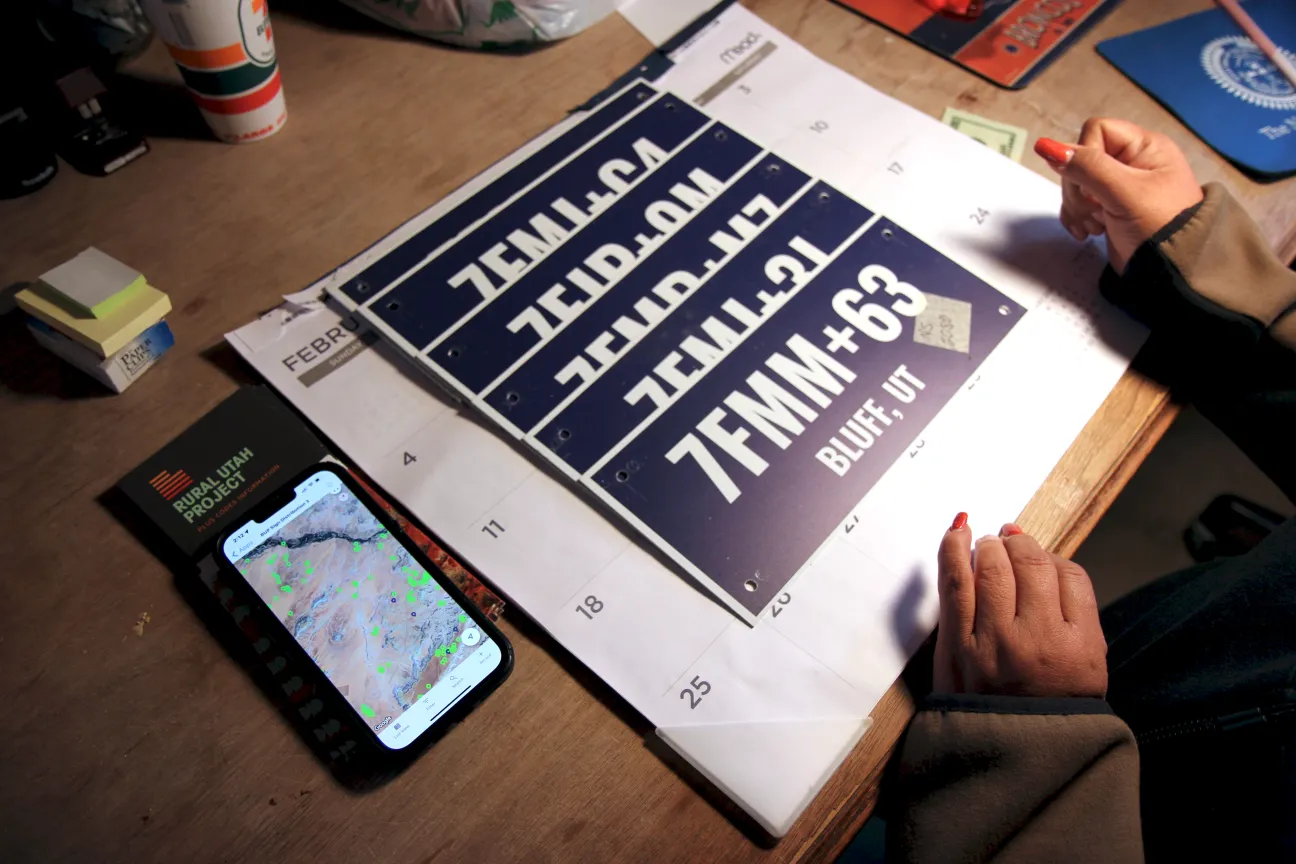

This fall, Sneak was one of over 3,000 residents on the Navajo Nation who received a new, more accurate address through an initiative led by a nonprofit called the Rural Utah Project. The new addresses, which were developed by Google, are called Plus Codes. The codes are simple alpha-numeric coordinates based on longitude and latitude.

All locations on Earth have unique, Google-generated Plus Codes, the same way every location on Earth has global coordinates, though the Plus Codes are much shorter than global coordinates, making them easier to share and remember.

Slow beginnings

Plus Codes aren’t new — Google started developing the free, open-source technology in 2015. But the system has been slow to catch on in some areas.

For the Rural Utah Project, whose main mission is to empower disenfranchised voters, educating people on how to use Plus Codes originally started out as a way to increase voter registration on the Navajo Nation.

While registering voters during the 2018 state and county elections, field organizers with the Rural Utah Project realized hundreds of residents on the Navajo Nation were registered in the wrong voting precincts because of mix-ups with their addresses.

“When I got my ballot, I noticed I had the wrong school board member that I was voting for,” said Daylene Redhorse, a field organizer with the Rural Utah Project who lives on the Navajo Nation and spearheaded the addressing initiative.

In rural parts of the Navajo Nation, as with many rural areas in the United States, step-by-step descriptive addresses are the norm. These addresses are valid for most services that require proof of residence, such as enrolling in public schools or registering to vote.

But just because these are technically “official” addresses doesn’t mean the system is particularly functional. For example, when Redhorse registered to vote with her descriptive address — 15 miles southwest of Bluff, Utah, County Road 436 — the county accidentally pinned her in a district north of Bluff.

“It’s discouraging for people, getting the wrong ballot and feeling like their vote doesn’t count,” Redhorse said. “As it is, we already have a lot of people who are skeptical about voting. When I go door-to-door registering people to vote, a lot of them say, ‘Why would I register? I don’t count. Nobody counts us.’”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.That attitude, Redhorse explains, stems from a long history of oppression and disenfranchisement for Native Americans, who didn’t receive the nationwide right to vote until 1962, when New Mexico was the last state to grant Native Americans suffrage.

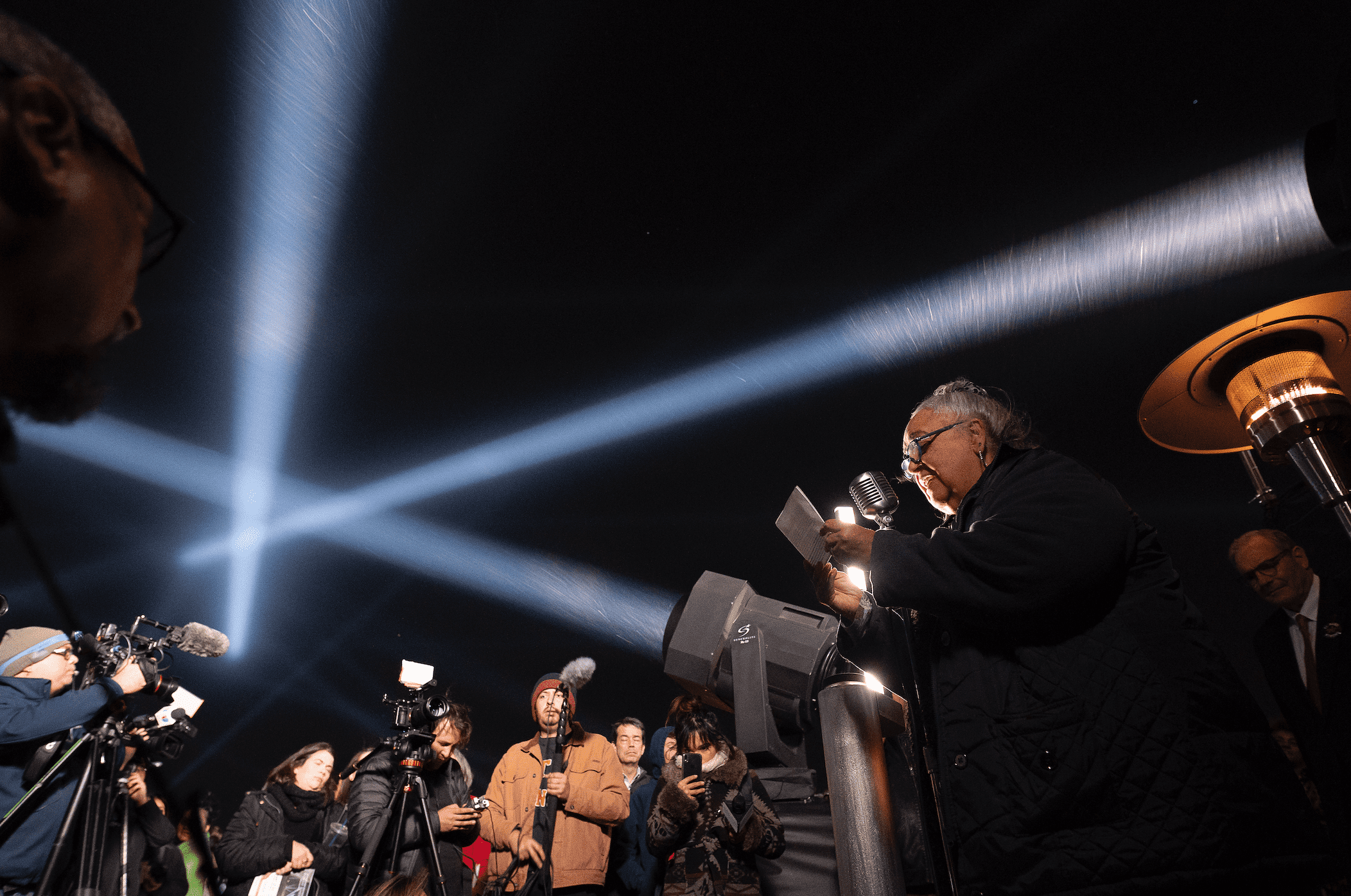

In order to help Utah residents on the Navajo Nation adopt the Plus Codes system, the Rural Utah Project partnered with Google, who helped field organizers match thousands of homes with their new addresses. Those Plus Codes were then printed on blue plastic signs, which were delivered door-to-door, along with information about how to register to vote.

Since starting the initiative, the Rural Utah Project has registered nearly 2,000 new voters with their Plus Codes.

A new address right on time

The day that field organizers arrived at Sneak’s house to deliver her Plus Code sign and explain the new addressing system, she had a seizure. Redhorse’s colleague, Tara Benally, called 9-1-1 and gave the dispatcher Sneak’s new Plus Code.

“They were able to use the Plus Code no problem,” Redhorse said. “They found the house easily.” Sneak is now able to use her Plus Code for her Life Alert system, which, her mother said, is a huge relief.

Herman Chee Jr., chief of the Monument Valley Fire Department, said that most EMS responders on the Navajo Nation already use Google Maps, which is compatible with Plus Codes, unlike descriptive addresses, which mostly rely on local knowledge to pinpoint.

“With our community, we just know where people live,” he said. But memory isn’t always perfect, especially during emergencies. He said there were many times when he made mistakes getting to the scene and had to double back.

“I remember one time, we got paged out to a structure fire. I was communicating with dispatch, and they just told me to take this road, then that road. And that was it. It was dark, and it was really snowing. I just had to guess. I could see the structure fire in the distance, but I still took that wrong turn. Had to go back,” he said. “Took a long time.”

He said Plus Codes have helped responders reach people’s houses faster. But the system only works if people remember to use their new addresses when calling 9-1-1. He was recently called out to a fire using a descriptive address.

“When I finally arrived, I saw that blue sign on their house,” he recalled. “I always tell people, use your Plus Code, remember your Plus Code. It’s so much easier for the dispatch.”

Beyond expectations

Redhorse said that when she started the addressing project for voter registration, she didn’t even think about all of the other benefits.

“Then we started to notice UPS coming down the dirt road, then FedEx coming down the dirt road.”

The United States Postal Service, which handles all voting by mail, doesn’t recognize Plus Codes. Rural residents will still need a post office box to receive mail-in ballots.

But commercial mail carriers, such as the United Parcel Service (UPS) and FedEx, have already started incorporating Plus Codes into their systems.

“I tell people to put their Plus Codes in the ‘description’ section when they’re buying something online,” Redhorse said. “The delivery person can usually figure it out that way.”

Residents can also use their new Plus Codes to receive at-home medical treatments, which were previously unavailable to them in some cases because of their addresses.

Redhorse used to work in a dialysis clinic in Blanding, Utah. For some of her patients that lived on the reservation, the commute was over two hours.

“The biggest complaint from our patients was that they didn’t want to make the drive every other day, but they couldn’t do home dialysis because they didn’t have an address that the insurance companies would recognize,” she said.

“One guy who used to be my patient used his Plus Code to get on home dialysis, and now I’ve been seeing the same truck that we used to have at the clinic going down the dirt roads,” she said. “When I see that I say, ‘Wow, this has really changed people’s lives.’”