From their first conversation, Nellie Goodwin knew that she and Sarah would make great roommates. For Nellie, 77 and recently widowed, Sarah’s sunny personality was a balm, and her weekend trips back to her parents’ house in the suburbs meant Nellie could still sometimes have the house to herself. For Sarah, who didn’t make a whole lot of money as a 25-year-old technical writer, the $600 Nellie charged for rent put pricey Cambridge, Massachusetts within reach.

The half-century between their ages didn’t faze either of them. “We were very connected,” says Goodwin, who found Sarah through a service called Nesterly that matches older and younger people as roommates. The idea is that each age group benefits from the arrangement in a particular way. For Goodwin, having Sarah around “made me feel less lonely after losing my husband.” And for Sarah, says Goodwin, “It gave her a place to live — housing prices in the Boston area are exorbitant.”

But services like Nesterly face a unique challenge during the pandemic. At the very moment when many older people who are acutely susceptible to Covid-19 could use extra assistance, it has become risky for them to be in proximity to others, making intergenerational cohabitation a fraught prospect. A while back, Sarah moved to Alabama, where her fiance is getting his doctorate. Goodwin, who suffers from chronic health issues, is now on her own again. “I feel very isolated in a lot of ways, but I just can’t take the risk,” she says, “I’ve been getting requests [through Nesterly] from kids who are coming back to school in the Boston area and are looking for a place to live, but I’ve had to say I’m sorry, I can’t.”

Once it’s possible to safely cohabitate again, however, such living arrangements may snap back quickly. Before the pandemic struck, Americans were beginning to drastically change their approach to who they live with. A 2018 survey found that nearly one in three adults were living with someone who is neither a parent nor a romantic partner. More than ever, people seem to be open to unorthodox living arrangements to solve their housing problems, whether those problems be affordability, loneliness or otherwise.

For older people, sharing their home with a younger person can allow them to age in place, which has many benefits, from preserving long-standing relationships to preventing cognitive decline. Such arrangements have grown in popularity. Whereas just six years ago, only two percent of adults aged 50 and up shared or rented out a bedroom or “accessory dwelling unit” in their homes, today 16 percent do.

“What is happening is that people are now thinking differently about housing,” says Danielle Arigoni, AARP’s Director of Livable Communities. In 2014, 59 percent of U.S. residents over 50 said they would not consider home sharing. By 2018, that number had dropped to 29 percent. “We are seeing a convergence of needs that are solved by this,” says Arigoni. “They [older people] want to stay in their homes, want to connect with other people and have income issues to deal with.”

Young people are no stranger to income issues either. According to a recent Pew Charitable Trust study, over 70 percent of Americans aged 20 to 34 rent their homes, and close to 40 percent of them are burdened with high rent. The average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in the university-heavy city of Boston, for example, currently stands at $2,500 per month, with rents near campus often higher. Brenda Atchison, a retired computer industry worker in her late sixties, rents out a bedroom in her townhouse to a public policy student at Boston University. “I’m not just renting rooms, that’s not how I feel about it,” Atchison, who lives in the Boston neighborhood of Roxbury, told BU Today. “When people walk into my home, they become an extension of my community.”

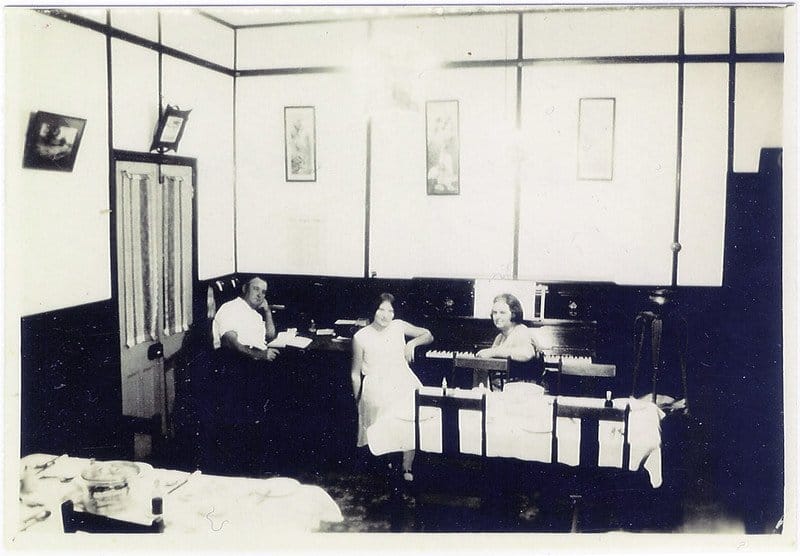

A housing solution with roots

Homesharing is, in a sense, a return to older ways of living. In an op-ed titled “Affordable Housing Is Your Spare Bedroom,” author Diana Lind explains in the New York Times:

Until World War II, American cities teemed with single-room-occupancy houses and hotels that served as de facto apartment rentals. In the 1930 census, 11.4 percent of urban families reported that they housed boarders. Many more families included grandparents and older relatives. These shared housing options let more people, more cheaply, enjoy a city’s amenities.

These boarding houses, once ubiquitous in cities, began disappearing as zoning codes and cultural attitudes changed, and single-family housing became the norm.

“Somewhere along the way we began… banning everything but a middle-class existence while making it harder to actually be middle class,” writes Michael Hendrix, director of state and local policy at the Manhattan Institute.

This led to a glut of oversized housing over time. Newly built homes in America now have an average 970 square feet per person, close to double the size of homes built in the 1970s. And even as those homes have increased in square footage, the average number of people living in them has gone down.

The result is an abundance of unused bedrooms. The real estate firm Trulia found that in the 100 largest housing markets in the U.S., there are nearly 3.6 million unoccupied rooms that could be rented out. New York has 177,000. Atlanta has 141,000. According to Trulia, the cost to rent out one of those rooms would be $24,000 less per year than renting a one-bedroom apartment.

“Rooming with strangers is not a new concept; it simply went out of fashion — except, that is, for the Millennial urbanite, whose roommates were merely an extension of the campus to the city,” writes Hendrix.

Given the convergence of supply and demand, intergenerational homeshare initiatives are bringing the boardinghouse model back at a moment when aging populations are presenting new challenges to cities.

There are about 60 senior/youth homeshare programs in the U.S. Some are decades old, others less than a year. There are independent free-market connectors, and government-sponsored programs to serve senior citizens. A few have become international platforms in the style of Airbnb, like Homeshare UK, which started in the late 1980s in London and has now expanded to 16 other countries. For young people who have grown up immersed in the “sharing economy,” services like Nesterly solve a housing problem the same way Uber solves a transportation problem or WeWork solves an office space problem.

“It is easy to see initiatives like Homeshare as peripheral, but there’s no reason why they can’t be mainstream, especially when the need has never been greater,” Homeshare UK CEO Alex Fox wrote in the Guardian this year. “The global Homeshare movement shows that this approach can be brought to thousands of people, and is in many other countries.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Laura Martinez, program manager for Toronto Homeshare, agrees. That city’s initiative started as a pilot program in 2018 and was made a permanent municipal program last year. The expansion came after the initial 12 participating pairs reported decreases in social isolation and financial burden from rooming together. “People said this would never work, that young people and old people don’t like each other,” says Martinez, “but it is funny, because we find they like each other a lot more if they are benefiting from each other.”

The data bear this out. According to the AARP’s research, older people’s reasons for sharing their home with a stranger tended to be practical: 58 percent wanted the renter to help with everyday activities, 50 percent did not want to live alone any longer and 49 percent wanted the extra income. Perhaps more important, about 75 percent wanted to stay in their current residence as long as possible.

Living together under lockdown

Even before the pandemic began, homesharing services faced challenges. Some cities were tightening the screws on short-term rentals — in some cases, for instance, limiting the number of unrelated people who can live under one roof. Services like Nesterly have avoided these restrictions by sticking to 30-day minimum stays, and essentially operating as matchmaking services, with both homeowners and prospective tenants posting their own online profiles. Before any agreement is struck, both parties preemptively come to terms on issues regarding rent, roommate etiquette and sharing of housework and other maintenance.

But the Covid-19 crisis presents a unique threat. The Centers for Disease Control recommends that older people limit their interactions with others as much as possible, and that those living with them do the same. Younger people, however, are less likely to adhere to social distancing rules, which could put their older roommate at risk.

Just before the pandemic struck, Nellie Goodwin had another young roommate who moved in after Sarah moved out. This one, named Skye, had moved to Boston from Iowa. Even after it became apparent that the virus was circulating through the city, Goodwin says Skye continued to take the subway, and at one point asked if her brother, who was visiting from Iowa, could stay with them. “I said absolutely not,” said Goodwin, who asked Skye to leave shortly thereafter. “She was too young. She just didn’t get it.”

To adapt, some homesharing programs are shifting their focus to support rather than cohabitation. Nesterly developed a new program called “Good Neighbors” in collaboration with the City of Boston. Older Bostonians can make requests via phone or online for things like “door-step deliveries” or even just friendly check-ins. Volunteers, who are provided masks and gloves by the city, make sure older residents get what they need. “This new volunteer platform will help organize and activate volunteers looking to help seniors who need things like groceries, medication, or just a good old-fashioned phone call check-in,” said Boston Mayor Marty Walsh in a statement.

These check-ins can feel like lifesavers themselves. “The isolation issue is particularly relevant during the pandemic,” says Raza Mirza, a senior research associate at the University of Toronto’s Institute for Life Course and Aging. “Many people now have a new awareness of the negative effects of being alone for prolonged periods, and it might inspire them to plan ahead so that they won’t face this situation in the future. I believe our post-pandemic solutions will have to be intergenerational. We need to re-imagine how we live, how we care for each other and how we manage the financial fall-out.”

Some are already doing that. One University of Toronto student, Lee Chang, had been living with her senior roommate, Catherine Tordoff, whom she met through Toronto’s homeshare program, when the pandemic struck. After discussing what they should do, Chang and Tordoff decided to continue living together, as safely as possible, to make sure Tordoff didn’t become isolated during lockdown. So far, it’s worked out. Chang picks up Tordoff’s prescriptions at the pharmacy, and both appreciate the company at a time when socializing is tough.

“I’m a very social person and quite active in my church, so I’m finding this hard,” Tordoff told the University of Toronto’s Factor-Intenwash Faculty of Social Work. “I’ve also been missing my daughter, who lives outside Toronto. Without Lee here, it would’ve been even more difficult.”