In New Zealand — the nearly Covid-free country where a lot of us wish we were right now — they have instituted a novel, laughably simple approach to get people to sort their recycling. They put gold stars on the bins of folks who properly sort their cans and bottles. It works — the amount of material able to be recycled has gone up from 48 percent to 80 percent.

The effort started when Christchurch was having a problem getting folks to sort their recyclables correctly, forcing the city to send these materials to the landfill. It turns out it’s too expensive to hire people to go through it all and sort it properly, and mixed up material “contaminates” the rest of the batch. It’s a pain in the ass on top of everything else.

The Guardian reported that Ross Trotter, a city council member, had an idea: rather than penalize those who didn’t sort their recyclables, the city would reward those who did — but not with cash. It was decided that the positive incentive would be a gold star stuck on the bins of folks who were doing their sorting correctly. It didn’t really cost the city anything, but it has had the desired effect.

Non-monetary incentives

It turns out Trotter’s idea is not unique — there are other instances of non-monetary incentives working better than cash to induce pro-social behavior.

Strathcona County, the area next to Edmonton, Alberta, does something very similar — and they added another public layer: neighbors can nominate one another for gold stars. Their stars aren’t as pretty as the ones in Christchurch, but it’s working.

Erez Yoeli, a research scientist at MIT who studies how altruism works, detailed examples of these types of awards succeeding in 2018 TED Talk. For instance, a power company wanted its customers to conserve electricity, so it sent them letters asking them to sign up for its energy saving program. But the response was not so great. So Yoeli suggested the company post the sign-up sheets in its customers’ building lobbies instead, where everyone could see the names of who had signed up. This tripled the response.

Another electrical company showed customers on their bills how much electricity their neighbors were conserving, which had the effect of tamping down excess consumption.

And when a get-out-the-vote organization added this sentence to their outreach materials: “You may be called after the election to discuss your experience at the polls,” voter turnout among recipients increased by 50 percent!

These types of social incentives often work even better than cash incentives. A survey of employees at 34 U.S. organizations, such as Universal Studios and the Postal Service, revealed that employees view monetary rewards simply as compensation — cash for the work they did, not as an incentive to change their behavior.

This would seem to conflict with classical economics, which says that a rational person would prefer money to a “worthless” gold star. Well, it turns out, just like when a teacher gives out gold stars in kindergarten class, the effect is social — the status of the recipient is elevated in the eyes of the group. Pretty soon, as with many of the New Zealand neighbors, everyone wants one, and strives to be worthy of the “reward.”

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.“A common thing is for people to postpone paying their taxes, and if you put a website up with their names, suddenly they’re real quick to pay their taxes,” says Yoeli. He says that people genuinely want to be SEEN as being good upstanding citizens, and if their good (or bad) behavior can be witnessed by others then it has a huge effect. “If you honor blood donors in a local newsletter, then they’re more likely to go back and give blood more often. It’s a pretty robust finding, and we often say it’s the lowest hanging fruit when it comes to motivating pro-social behaviors.”

Of course, there were folks in Christchurch who never managed to sort their recyclables properly — their sorting bins were eventually removed after numerous failures and their stuff automatically went to the landfill. Not everyone cares what other people think. Maybe that’s okay.

Cash perverts values

Over the years, studies have found that monetary rewards alone have only a short-term impact, and can even lead to a lust for more money, an increase in pay dissatisfaction and eventual unhappiness at work.

I read a book a while back called The Moral Economy by Samuel Bowles. In his behavioral experiments he found that people will, by default, behave in a pro-social way in many cases… and that cash rewards and incentives can actually diminish good behavior, leading people to see themselves and others as solely self interested (ye olde classic rational economic human). In a nutshell, Bowles sees people as having civic virtues, but warns that these can be perverted — in his words, “crowded out” — when their behaviors are made to be transactional.

He relates an experiment that Daniel Kahneman mentions in Thinking, Fast and Slow. An Israeli daycare center was annoyed by parents who showed up late to pick up their kids. It decided to fine the latecomers. Rather than decreasing tardiness, however, these small fines had the opposite effect — lateness actually increased as folks saw payment of the fines as permission to show up late.

In an interview with RTBC, Yoeli suggests that public cooperation has enabled the very success of the human race: “There are anthropologists who have documented that this is a key distinguishing feature between humans and other primates and why humans are able to cooperate at such a large scale while other primates can’t.”

I’m not sure I agree that animals are not also cooperative, but I do agree that cooperation is often nudged by social status and public observability, which makes it a mighty lever.

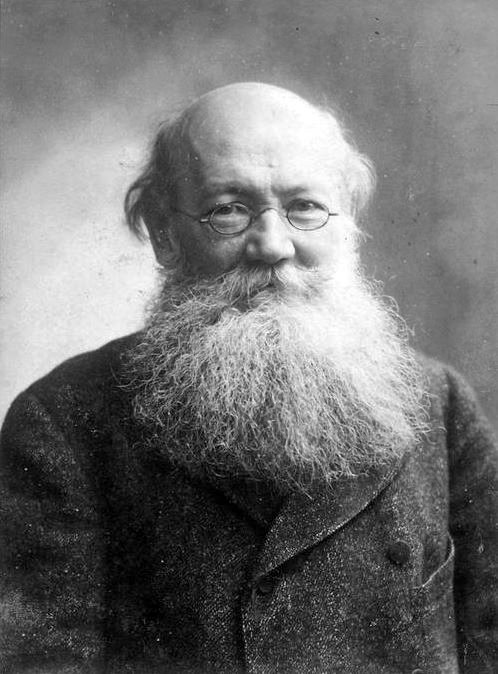

This brings us to the mutual aid theories of Peter Kropotkin, a multi-hyphenate who died in 1921.

His story is long, strange and fascinating. He spent some formative years in Siberia, observing the wildlife and Indigenous People in that harsh environment. He came to the conclusion that there were behavioral and evolutionary forces at work that defied “social darwinism,” the theory that life is a ruthless game of survival of the fittest. Kropotkin observed what he called mutual aid, in which Indigenous People and animals helped one another to survive. They engaged in cooperation rather than competition red in tooth and claw. This led him to believe we have an evolved tendency to work together…an aspect of Darwin’s theory that had been often overlooked.

This informed Kropotkin’s opinion that people don’t need big governments to work together. For these anarchist views he was arrested in Russia and France. (In Russia he escaped from prison with the help of a friend and they went to a fancy restaurant: “They’ll never think to look for me here.”) He eventually spent time in England, becoming a friend of George Bernard Shaw and William Morris. He was not a Marxist — he believed that labor should be viewed as more than a mere commodity. I certainly don’t subscribe to all his views — he’s a bit of a rebellious revolutionary anarchist wild card — but I suspect he might like the gold star approach.

Additional reporting by Eric Krebs