Ralph Gerber* has tried nearly everything a wealthy alcoholic can try during two decades of excessive drinking: half a dozen stints in rehab, Alcoholics Anonymous, even a shaman-led quest through the Arizona desert. Each time, the treatments got him sober, yet the 48-year-old real estate broker in Los Angeles kept relapsing. His divorce, problems at his firm, the Covid lockdowns — there was always a trigger that sent him back to the gin.

In the spring of 2021, he decided to try a path that is not entirely legal. He flew to Denver, Colorado, to take a dose of psilocybin, the hallucinogenic component in magic mushrooms. “It was a journey into my innermost core,” is how Gerber describes the six-hour experience. “I felt flooded with love and was able to get in touch with long-suppressed feelings.” Six months later, he made the trip again for a second session. “I have been sober ever since,” he says proudly, half confident he’s reached the end of his addiction, half fearful the effects might eventually wear off.

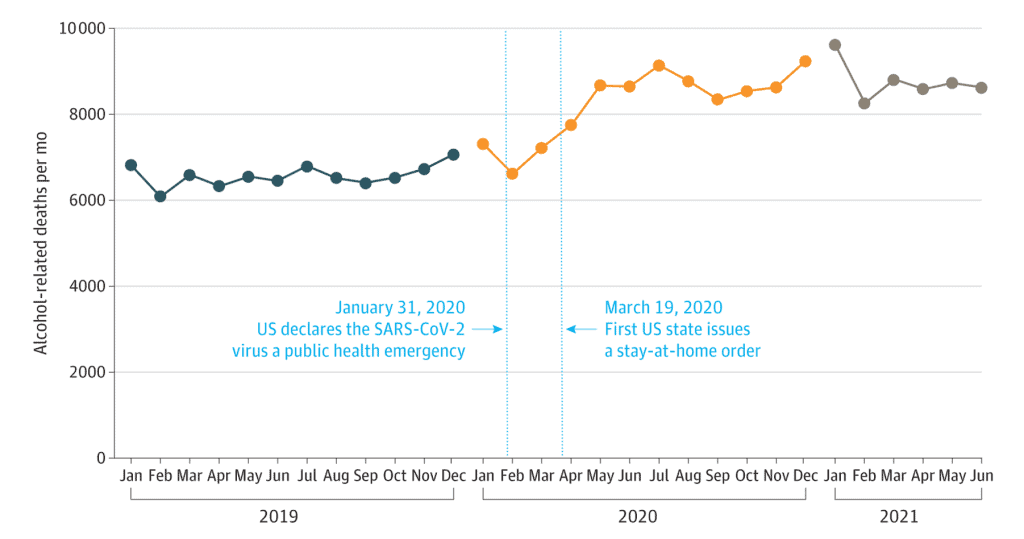

The need for effective treatments for alcohol dependency has been made more urgent by the pandemic. A major study released last week found that alcohol-related deaths have surged during Covid-19, killing over 99,000 Americans in 2020 — 25 percent more than the previous year. In fact, in 2020 alcohol killed more non-senior adults than Covid itself.

This public health crisis didn’t emerge out of the blue — alcohol consumption has been rising steadily in the U.S. for years. Alcohol-related deaths doubled between 1999 and 2017, a key reason life expectancy fell during that time. Yet effective treatments have proved elusive. Now Gerber, and a growing number of therapists and scientists, are betting on psychedelics as a promising therapeutic for alcohol addiction.

Nearly 15 million American adults struggle with alcohol use disorder, and many try in vain to find lasting therapeutic success. While Gerber raves about the emotional experience of his psilocybin trips, a multidisciplinary, international collaboration has for the first time shown the exact physical mechanism behind the potential treatment.

Led by Marcus Meinhardt, a neurobiologist at the Central Institute of Mental Health in Mannheim, Germany, the researchers uncovered how psilocybin restores molecular circuits in the brains of people dependent on alcohol, thus contributing to reducing relapses. Many people who are addicted to alcohol, cocaine and nicotine show damage of a specific glutamate receptor: mGluR2. Put simply, Meinhardt compares this receptor to “an antenna that receives signals in the brain. When these signals cannot be processed, behavior patterns surface such as the craving for alcohol. With psilocybin, we can render this receptor functional again.”

A single dose of psilocybin sufficed in Meinhardt’s experiments with rodents to change their addictive behavior. Provided these results can be replicated in humans, it would signify a major breakthrough in addiction therapy. “When you consider that many addicts take medication two or three times a day, often for life, this would be a seminal success,” the normally restrained scientist says while cautioning against excessive optimism. “We have to do more research. How long does the effect last? What exactly happens in the brain? Does psilocybin only affect the brain or the entire body? We need answers to these questions before thinking about legalizing psilocybin for therapy.”

Meinhardt is planning to uncover those answers by moving on to humans for his next study. Since 2018, his university has partnered with three others in Switzerland, Italy and France to focus specifically on researching the potential of psilocybin in alcohol addiction.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.After completing a psilocybin study with 60 depressive patients, neuropsychologist Katrin Preller at the University Zürich, one of Meinhardt’s colleagues in the PsiAlc collaboration, started a study with 60 alcoholics last year. While she can’t reveal the preliminary findings yet, she calls the results thus far “very, very promising.” The first study about depression “shows that patients with mental health issues do significantly better after one or two psychedelic treatments under medical supervision.” She hopes to get similar results with the ongoing addiction study.

But she admits that even experts like her who spent a decade studying the effects of drug use on the brain don’t fully understand all the changes psychedelics cause. “To really speak of an effective therapy, we need bigger, controlled studies.” TLegal restrictions have made it nearly impossible in the last 30 years to conduct such studies, and one of the problems with double-blind controlled studies involving hallucinogens is that recipients can usually tell if they get a placebo or the real deal.

Michael Pollan’s bestseller How to Change Your Mind fueled the renaissance of psychedelics, not least because the initially skeptical author turned into a true believer after repeated trips with the drugs. His widely popular book brought public awareness to the numerous world-class research institutes focusing on the therapeutic benefits of psychedelics, especially psilocybin and LSD. Renowned universities such as the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Yale and UCLA have announced early signs of success, indicating long-lasting positive changes.

“One of the remarkably interesting features of working with psychedelics is they’re likely to have transdiagnostic applicability,” Roland Griffiths told Scientific American. Griffiths heads the Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research and has led some of the most promising studies evaluating psilocybin for treating depression, nicotine addiction and alcoholism. Two-thirds of psilocybin patients at Johns Hopkins described the trip as “the most meaningful experience of their lives.”

Cities such as Denver, Oakland and Washington, D.C., have already legalized psychedelics for therapeutic use, and more cities and states, notably California, have announced similar plans (though the drugs remain illegal under federal law.) In Switzerland, psychiatrists can request the “compassionate use” of psychedelics for depression, posttraumatic stress and addiction.

Of course, LSD and psilocybin were hailed as miracle cures in the past, when Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary famously roused his followers to “turn on, tune in, drop out.” Some of the old LSD gurus, including psychiatrist Charles Grob at UCLA, are rebooting the research they started in the ‘60s, but with a focus on medicinal instead of spiritual use. By founding the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), psychologist Rick Doblin has found a mighty lobby for legalization and multi-million dollar research funds to find scientific arguments for changing the laws.

Meinhardt is familiar with the old and new studies, but does not want to raise unjustified expectations. “In the ‘60s, we saw a lot of LSD research with strong results in terms of alcohol and heroin addiction,” he says. “But when LSD was declared illegal in 1970, all research funding stopped, and the users went underground. I believe that both people and scientists were too euphoric back then. We need to learn from these mistakes and present solid research before suggesting legalization.”

After all, even though the hype surrounding psychedelics is mounting, taking them is not without risk. Psychedelics can trigger high blood pressure, irregular heartbeat or psychosis. Therefore, most current psilocybin studies exclude patients with heart issues, hypertension or schizophrenia in their family background. “A single, carefully curated dose under medical supervision is entirely different than taking psychedelics at a party or a festival,” Preller says.

Nevertheless, a growing number of users are calling for legalizing psychedelics. While the catastrophic effects of alcohol (a legal drug that kills more Americans than drug overdoses) are well-documented, both users and experts point out that psilocybin is not addictive. “Alcohol has destroyed everything meaningful in my life — my health, my marriage, my relationships,” Ralph Gerber says. “The mushrooms have at least shown me the possibility that I can still turn the corner.”

*Name changed at the request of the interviewee