A recent report by the think tank TransitCenter summed up America’s transit funk. It showed that U.S. public transportation ridership has fallen 14 percent since 2013.

The problem, the report found? The competitor. “Despite all the changes that we see in transportation technology, it’s still really ‘transit versus the private automobile’ in most cities,” coauthor Steven Higashide told GovTech, a government trade publication.

While there are some notable exceptions to this trend — Seattle, for example — there is one that stands out a little unexpectedly: Columbus, Ohio. And true to their rustbelt roots, the solution they’ve found is uniquely homegrown. Since summer, 2018, Columbus has dramatically increased the number of downtown workers taking transit with a solution typically scorned by transit professionals: free transit.

A surprisingly simple solution

Columbus’s road to increased transit ridership started where many discussions around public transportation do: a lack of parking downtown.

Unlike most Midwestern cities, Ohio’s capital is growing fast. Since 2000, its population has ballooned by 25 percent with much of this growth occurring in the city center. It is the seat of state government and the regional center for the expanding financial services and insurance sectors. It’s also home to Ohio State University, the fourth largest college in the country by undergraduates. In short, Columbus has become something of an unexpected boomtown, its central core abuzz with residents and workers.

Columbus also happens to be one of those cities where people tend to drive to work. As the city center became more and more squeezed for space, a growing number of downtown workers were paying $150 to $200 per month to park there. Adding more parking would have been tough — the city’s zoning restrictions would have made it expensive — and encouraging even more car use also didn’t seem like a sustainable fix.

So local business leaders came up with a simple solution: they would give everyone who works downtown a free bus pass and they themselves, the local businesses, would pay for it.

It works like this: Each business pays a fee (three cents per square foot of leased space they occupy) and the money goes to pay for the free passes. Whether the employees want to use the passes is entirely up to them. The model is simple, sure, but still surprising: private businesses aren’t typically known for personally subsidizing mass transit. But a simple look at the pricetag shows why it makes sense for the businesses to support: under the property assessments, the average free bus pass costs businesses about $40 per year, per employee — a pretty light lift for most companies, especially compared to the cost of building parking infrastructure.

“We didn’t really run out and try to sell mass transit to the business leadership on a macro level,” says Cleve Ricksecker, executive director for Capital Crossroads, the downtown business association that originated the free pass idea and oversees the property assessment program that pays for it.

Under this model, employees can drive to work on certain days and take the bus on others, depending on what else they have to do that day. Heck, they can even use the passes to get around by bus on the weekends.

The model is also unique in the control that the employee has over signing up. For example, they can use an app on their phone or get their pass directly from the transit agency, instead of having to fill out forms with the human resources’ office at their company. This removed a lot of friction for the user.

“We learned early on that the businesses didn’t have the will or the economic ability to build more parking garages, and the best way to sell this idea was to basically give the employees a pay raise by taking the cost of parking away. And we found the best way to do this was to give them a different way to get to work besides driving,” says Ricksecker. “Both the employees and their employers bought in on that, because of the benefits both got.”

The proof in the parking lot

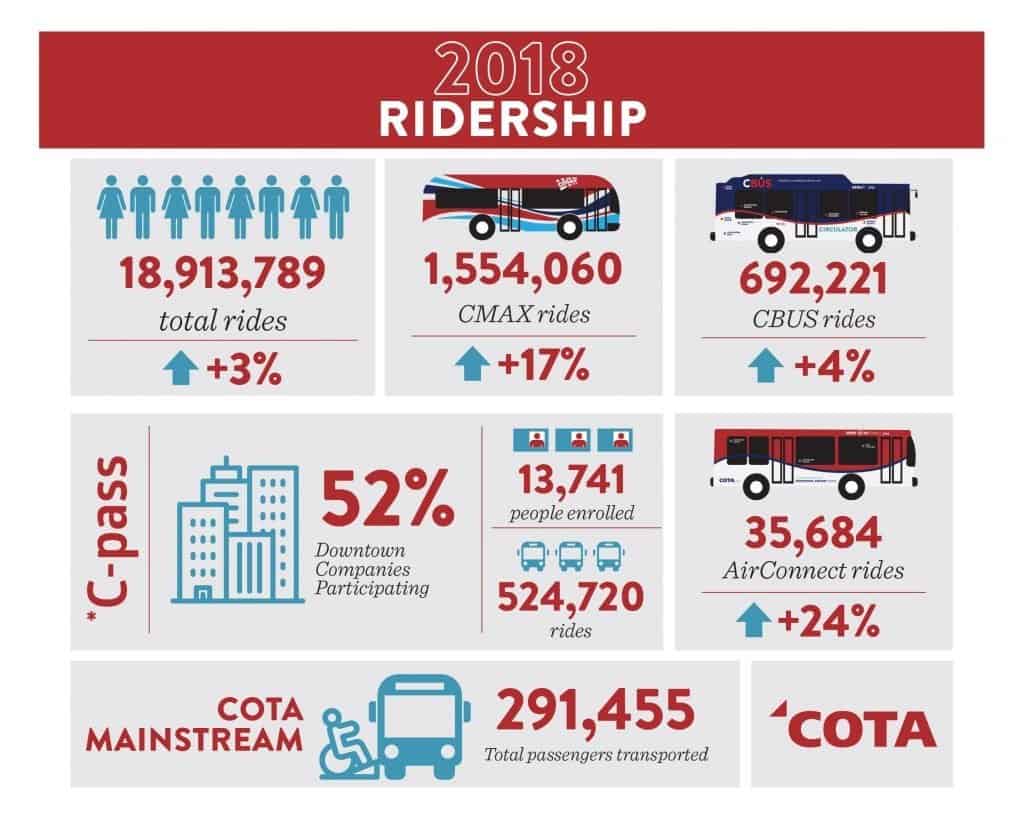

The results since the program launched in June 2018 have been impressive. Before the C-pass program, as it’s called, only five percent of downtown workers commuted by bus. Today, about 430 companies have enrolled in the program and about 14,800 workers — close to 15 percent of the downtown labor force — have used it, accounting for more than one million bus rides in the first year.

The increase in ridership is particularly remarkable given that 93 percent of those using the free bus pass have access to a private car. This means that it’s not only people with no other option who are taking advantage — the program is genuinely convincing commuters to choose transit over driving.

What’s more, the program’s users are evenly divided by income levels: 20 percent make less than $50,000 per year, and 19 percent make more than $100,000.

The total cost to the businesses paying in, along with other contributions, is about $5 million per year, with that money going to the Central Ohio Transit Authority (COTA). The downtown business association estimates that the program has freed up 2,400 parking spaces — the equivalent of four downtown garages — and allowed for 2,900 additional people to work in the district.

The result has been a boon to downtown workers, who are saving more than $5,000 annually in gas and parking expenses. But the city itself has benefited, too. New mass transit routes are being developed that, because of the ridership increases, are designed for the city’s population more generally, rather than subgroups. For instance, instead of routes that meander from hospitals to grocery stores to courthouses, COTA is putting direct corridors in place with straight-shot, point-A-to-point-B routes.

“What we are trying to do is make the transit system we have work better, with shorter times, and the service more reliable,” says Columbus City Council President Shannon Hardin. “We can’t solve transportation problems by adding more lanes to the highways. If you make the mass transit system more reliable and timely, people will use it because they are hungry for another option besides their car. This downtown pass program is proving that.”

The free bus passes are also helping the city compete with the suburbs for workers, as express bus service from the far suburbs to downtown went up 17 percent in the second half of 2018 alone. Bus ridership in general has increased 24 percent at rush hour.

In the towns north of Columbus, offices and retail developments have acres of free parking. But by making its buses free, downtown Columbus is reclaiming the advantage, leveraging the benefits of proximity in a way that has found broad appeal (free wifi service on the buses helps). In a recent survey, more than a third of downtown businesses said that the program helped them recruit and retain employees, and 13 percent said that the program impacted their decision to sign or renew a lease downtown.

Just like you

“When we first started talking about this free pass system as a possible solution to various transportation issues in Columbus’s downtown area, most of the so-called experts said, ‘No one wants to ride the bus, this will never work,’” says Daniel Dunsmoor, executive vice president of Colliers International, a real estate broker with offices in downtown Columbus. “But we found that people who say no one rides the bus are people who never ride the bus. What is happening with this Columbus free pass program is that co-workers are talking to each other, telling each other what works and what doesn’t, and that’s why we see it succeeding so well.”

That speaks to what has perhaps been the program’s greatest success: it has shifted the public’s perception of who uses transit to commute in the city of Columbus. No longer is the bus something that other people take to work. Now, it’s the way your colleagues, your assistants, your interns and even your boss get to the office, just like you.

The big question is: is it replicable?

“I do think this approach can work in other cities, but they have to change their thinking a bit,” says Joshua Lapp, a mass transit advocate and urban planner with the Columbus-based firm Designing Local. “This only works when you think of mass transit as having a very broad range of users. Too often mass transit tries to sell to one group and excludes others. This program was for anyone who worked downtown. That’s pretty broad.”

—

This story is part of a collection called Pay for What You Get: Stories about paying for the true costs of how we use cities. Read more here.