The following Q&A is the product of two separate interviews that have been edited and condensed.

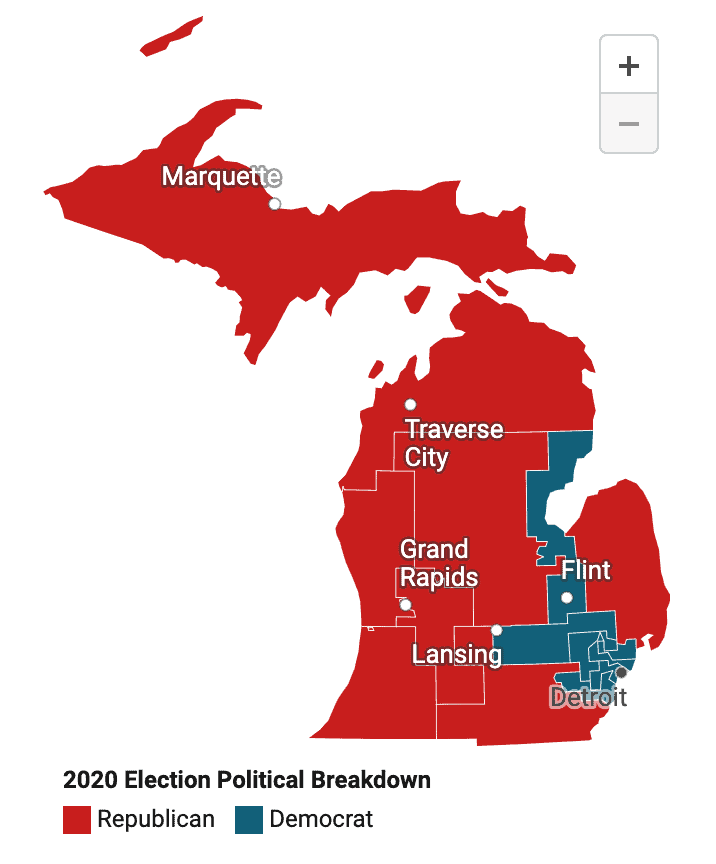

This year, Michigan is preparing to hold the most competitive election the state has seen in decades. It has completely redrawn its congressional districts, changing from a state that was heavily gerrymandered to one that allows for fair and competitive elections. We ran a story in 2020 about the citizen-driven campaign that led to this moment. Now, the state’s congressional maps have been redrawn in a way that lets voters — and not politicians — determine who will represent them.

Why this matters

In the United States more than 90 percent of federal voting districts have been drawn in such a way that their election outcomes are more or less predetermined. Only 40 U.S. House seats out of 435 are considered competitive. Clearly, this is NOT democracy.

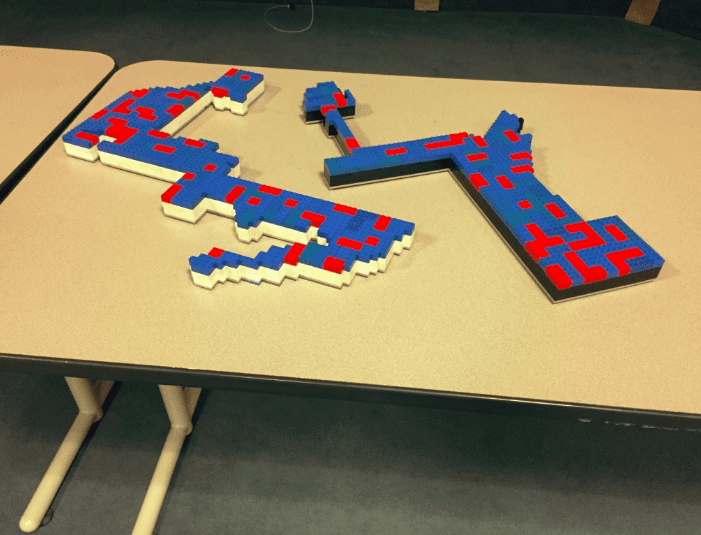

This clever mapmaking is called gerrymandering and it comes in two flavors: packing and cracking.

In packing, the party in power draws the maps to concentrate the opposition’s voters into a single district, leaving them uncompetitive in all of the surrounding districts. Cracking is exactly the opposite. The party in power draws the lines so that the opposition’s voters are scattered across many different districts, making them an electoral minority in all of them.

Through this kind of creative map drawing, politicians are in effect choosing voters rather than voters choosing politicians. Both parties do this, and it’s hard to fight it because once the lines have been drawn to one party’s advantage they generally want to keep it that way. Which is why the best way to break the gerrymandering cycle is to take it out of the hands of politicians altogether.

Michigan did this, and other states can, too.

How Michigan Did It

Step 1: Passing a ballot initiative

In 2016, a young woman named Katie Fahey posted a comment on social media:

The response was enormous, and by the following year her appeal had birthed a nonprofit, non-partisan organization called Voters Not Politicians. VNP’s goal was to get enough signatures for a ballot initiative that would allow Michigan’s district lines to be redrawn — this time, by voters, not biased political interests.

After a lot of legwork and creative door-to door campaigning, they did it. The ballot initiative, Michigan Proposal 2, passed in 2018 and this past year the state’s congressional lines were redrawn. Politicians were expressly excluded from the process.

With Michigan’s first un-gerrymandered elections coming up this year, I decided to follow up with Jamie Lyons-Eddy and Kim Murphy-Kovalick at Voters Not Politicians. I also spoke to Rebecca Szetela, Brittini Kellom and Doug Clark — three of the 13 folks who actually re-drew the district lines. I talked to them about how it all happened.

David Byrne: As you probably know, we ran a piece in 2020 after the ballot initiative passed, and now we’re celebrating the fact that the redistricting has actually happened without politicians involved. So first of all, I want to hear how a grassroots campaign can get an initiative on the ballot without the politicians either getting rid of it or digging into it and making it work for their ends.

Jamie Lyons-Eddy: They tried, but we were so under the radar when we started. It literally was that Facebook post from Katie Fahey who was then 27 years old.

I was one of the original people who answered that Facebook post, as was Nancy [Wang]. Nancy is now the executive director [of VNP]. We happened to have the exact right group of people come together and we were so excited and motivated and serious.

I was the only person who had knocked on a door before, so I turned out to be the field director and I organized the 428,000 signatures that we turned in. We somehow did it all with volunteers — the day we turned in all those signatures we had no one on payroll. We made Katie quit her day job after that, to run the organization.

David Byrne: In Michigan, if you get the 316,000 signatures an initiative can go on the ballot…

Jamie Lyons-Eddy: Correct. A constitutional amendment requires 10 percent of the votes cast in the last gubernatorial election. So our requirement was 316,000 signatures, but we overshot that. We had 4,000 people collecting signatures around the state.

Note: Michigan is one of a handful of states in which citizens can add an initiative to the ballot. In states where that is not the case, it would be much harder to make this happen.

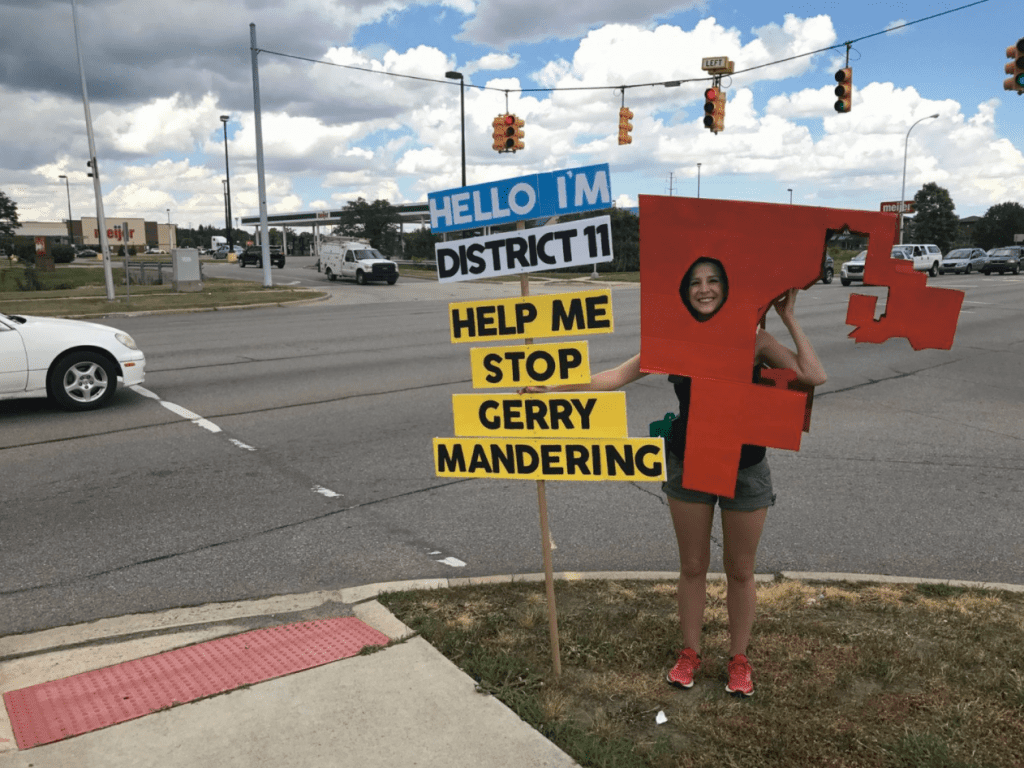

David Byrne: Is that where you had all these costumes and other fun ways of drawing attention to this issue?

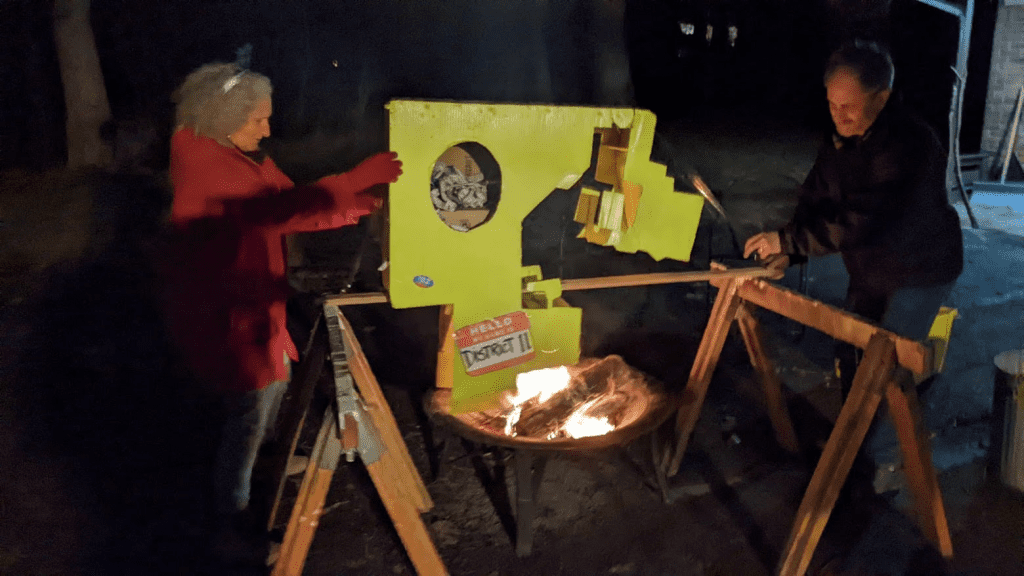

Jamie Lyons-Eddy: Usually a signature collection effort like this doesn’t convert very well into a campaign, but we ended up having thousands of people who campaigned for Yes on 2. We continued with the costumes and the songs and the buttons and the signs and all that kind of stuff.

Once we were on the ballot we actually survived a [Michigan] Supreme Court challenge. We thought survival was unlikely because it was a Republican-controlled Supreme Court. Once we got past that, we got a lot of funding from big funders. But still, we kept that grassroots energy going.

David Byrne: How do you think you survived that challenge? On paper, it seems very unlikely.

Jamie Lyons-Eddy: There was a particular justice — Justice [Elizabeth] Clement. There are some judges and justices who are more interested in actually following the law than the politics, [and while] they’re maybe nominated by one party or another they’re not strictly partisan. She did the right thing. There was nothing wrong with our language. There was no real reason to kick it off other than a political reason, and they declined to do that.

David Byrne: When you’re out there trying to get people involved, going all over the place, how do you explain gerrymandering? It’s a complicated thing. I mean, if you just knock on somebody’s door: “We’re trying to end gerrymandering.” They might go, “Well, who’s that?”

Kim Murphy-Kovalick: It had become part of the national conversation. At that point, we would use those maps and we would show people where they lived and say, “Look at Saginaw [a county and city in Michigan]. The districts are actually split in half between the city and the township. Why do you think that is?” And everybody who lives in those areas gets it right away.

We used that in these town halls all over the state as a way of teaching how gerrymandering actually works. There was a brilliant ad campaign at the end, kind of that cartoon-style stuff.

Step 2: Drawing a new map

So, after Voters Not Politicians got this ballot initiative passed, the task of redrawing the actual map fell to a commission of citizens who identified with different political parties.

I interviewed some of these commission members to ask how this process actually worked. Brittni Kellom is aligned Democratic, Doug Clark is aligned Republican, and Rebecca Szetela isn’t aligned with either major party.

David Byrne: How exactly were these random members of the commission selected? I know there were four who self-reported as Democrats, four as Republicans and five as non-aligned with either party. How were those people found?

Doug Clark: We had a campaign by the Department of State to advertise for commission members and that was done through a number of publications and TV ads and so forth. There was an application form you needed to fill out and commit to about 15 different criteria such as availability, what the pay scale would be and so forth. There were 9,300 applicants.

David Byrne: Woah.

Doug Clark: Yeah, it was quite a bit. To narrow that down, the Secretary of State randomly selected 200 people out of the 9,300, and those 200 applications got sent to the legislature, which had the ability to review those and eliminate a certain number of people. They brought it down to about 180, I believe. Then the Department of State in Michigan hired a firm to come in and randomly select the four Democrats, four Republicans and five non-partisan people. So that’s how the commission was formed. And the commission worked very well together over the course of the year and a half we’ve been together.

David Byrne: When you say “worked well together,” that leads me to my next question. What happens if there was a disagreement? If someone’s proposing a line on the map and someone else goes, “No, no, no.”

Rebecca Szetela: There were definitely disagreements, there’s no doubt about it. Every minute of our meetings was filmed and recorded and there were times when things got heated, there were times when people disagreed. But I think there was a baseline respect that people had for each other and for the process, and people would talk things through. Sometimes we would take a strategic break and let everyone walk around and stretch their legs and come back to the table. And we were able to work through all the differences.

David Byrne: What is the actual process of drawing the new lines?

Rebecca Szetela: We made a decision as a commission that we were going to start from scratch, and that was based on public feedback we had received that they didn’t want us starting with or referring to the old maps. We divided the state into regions, and then we started going down our list of criteria. We started drawing maps based on communities of interest, and then we moved on to the Voting Rights Act, and then we started looking at partisan fairness, and we just tried to be systematic in going down the list, drawing maps and constantly making adjustments. We came up with multiple maps for each type of district to allow for alternative theories on how we should draw lines. And then those ended up being presented to the public.

David Byrne: When you say “communities of interest” does that mean communities that are known to vote one way or another?

Doug Clark: Not necessarily. It often means people who have things economically in common. People with certain jobs in common such as farming, such as manufacturing, because we do have those pockets in Michigan. Religion — we have a huge Arab-American community, a huge Bangladeshi community and a huge Amish community in Michigan. Our view was not political, that was not one of the major factors of communities of interest at all.

This was counter intuitive to me — I would have thought they would have looked at past voting records, demographics, income, etc. To me, their approach to “communities of interest” cleverly avoids focusing on politics.

Rebecca Szetela: I would add that the definition of communities of interest was very flexible so that voters could come to us and say, this is my community of interest and this is what I think you should incorporate into the map. And the commission would then take that information and weigh it along with other requests. So it was a very flexible process.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.David Byrne: Okay, so people start drawing the lines on a map. What kinds of conversations happen then, about adjusting the lines and redrawing and all that sort of thing?

Rebecca Szetela: We actually took turns. One commissioner would take a turn and draw a district, and then it would be passed to another commissioner and they would add on or make adjustments. We did it very much collaboratively. If there was a significant dispute or difference of opinion about where the lines should be placed we would create what we called an alternative map, and so maybe we would have one map that would have those two cities together and another map that would have those two cities apart. We came up with lots of alternatives, everybody’s ideas were allowed to be incorporated, and ultimately we refined those down to what the public supported at our final hearings and voted on one of those maps.

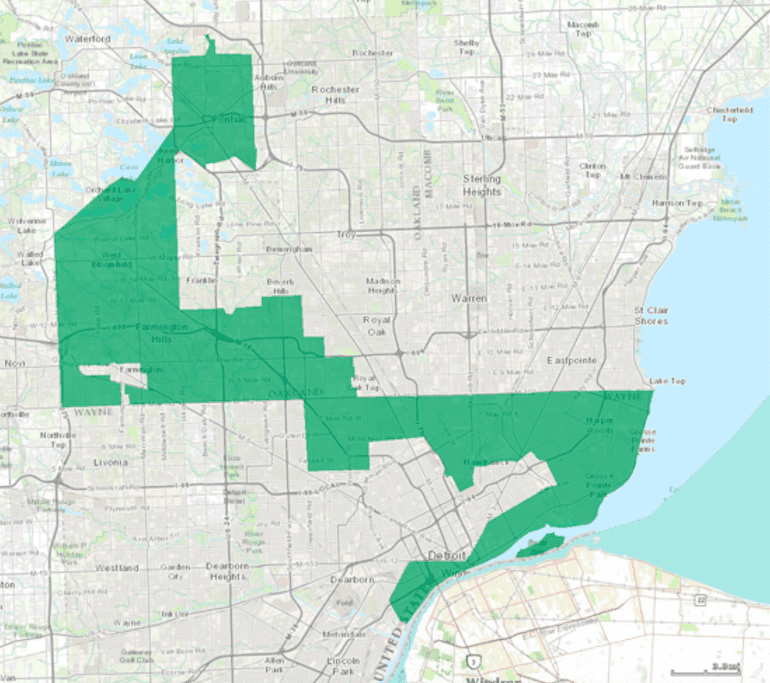

David Byrne: I read that Black voters in Detroit had an issue with the fact that they were going to be divided up into different districts. They felt they were going to have less representation than they might have under the old district lines and this became an issue. How was that resolved?

Rebecca Szetela: The historic districts in Detroit [a city that is about 77 percent Black] were extremely packed, so much so that our voting rights expert was actually shocked at how concentrated these districts were. You would have 80 to 90 percent what we call BVAP, which is Black Voting Age Population, and so using the data we had from our expert — Lisa Handley was her name — we could actually go with much lower BVAP percentages [in the newly drawn districts] and still allow minority voters to elect their candidates of choice.

David Byrne: So in unpacking that district, there was a consideration that people in that district could still have some representation in the various new districts.

Rebecca Szetela: We followed that advice and the advice of our voting rights attorney as well, and we drew districts that had lower percentages [of BVAP voters] than they had had before, which actually resulted in there being more districts where those voters should be able to elect their candidates of choice. So I think at the end of the day it should result in better and more representation.

Step 3: Getting the maps accepted

David Byrne: Did the legislature or the courts get involved at any point?

Rebecca Szetela: So the legislature did not get involved at all and the process was specifically designed to not have the legislature be involved. The whole point of the commission was to have people who were not actually politicians to draw the lines. We did have some court decisions that came down while we were drawing, but it was not related to the drawing of the lines itself. We had one issue that had to do with the timing of getting the maps done that was before the courts. The courts were not involved with the process at all while we were drawing the lines.

Jamie Lyons-Eddy: What we required in the amendment is you have to have a majority to vote the maps in. So two of the Republicans, two of the Democrats, and at least two of the unaffiliated had to agree on the maps. And they did… There was a process if they got deadlocked and couldn’t get there, but they never had to go to that process.

They did what politicians all over the state and the country can’t do. They came together across parties and agreed on these maps. Which we think is just an enormous success.

David Byrne: I assume these new lines will apply in the next election.

Rebecca Szetela: As far as we know, they will. We have had one challenge from the Detroit caucus plaintiffs group that was dismissed by the Michigan Supreme Court. We had another challenge in the Western District of Michigan where a portion of that has been dismissed as well, and we still have one portion of that pending. And we have a current lawsuit by the League of Women Voters that’s before the Michigan Supreme Court that no action has been taken on. So as of right now, it appears the maps will be used in the upcoming elections and that will continue until we hear otherwise from the courts.