At the end of June, the World Health Organization certified China as having eliminated malaria. The announcement may have gotten a little drowned out by the mass spectacles surrounding the Communist Party’s 100th birthday, but make no mistake: going from 30 million cases annually to zero really is a reason to be cheerful.

There are a lot of places that would like to emulate China — malaria is one of the top public health threats around the world, with 200 million cases and 400,000 deaths per year. And while a number of other countries are malaria-free — most recently El Salvador, Algeria, Argentina, Paraguay and Uzbekistan — many more are eager to know how the Chinese did it.

What did China do?

The scope of China’s achievement is hard to overstate. In the 1940s it had 30 million annual malaria cases and 300,000 deaths. The disease was endemic across 70 percent of the country, and with no good treatment China’s health and social infrastructure was buckling under its weight. In the ‘50s China had only 20,000 physicians practicing Western medicine, so there was little in the way of what is often thought of as modern medicine today.

With all this pressure, Mao Zedong made combating malaria a priority in the early 1950s, and in 1967 the government began something called the 523 Project, an initiative that pulled together 500 scientists from 60 institutions to find an effective treatment. By this time the parasite had developed resistance to the existing treatment and was resurging as a result. The quest had taken on new urgency.

One of the scientists assigned to find a new treatment was a woman named Tu Youyou.

Treatment: hidden figures

When Tu Youyou was assigned to the 523 Project in 1969, over 240,000 compounds to treat malaria had already been tested. None of them worked.

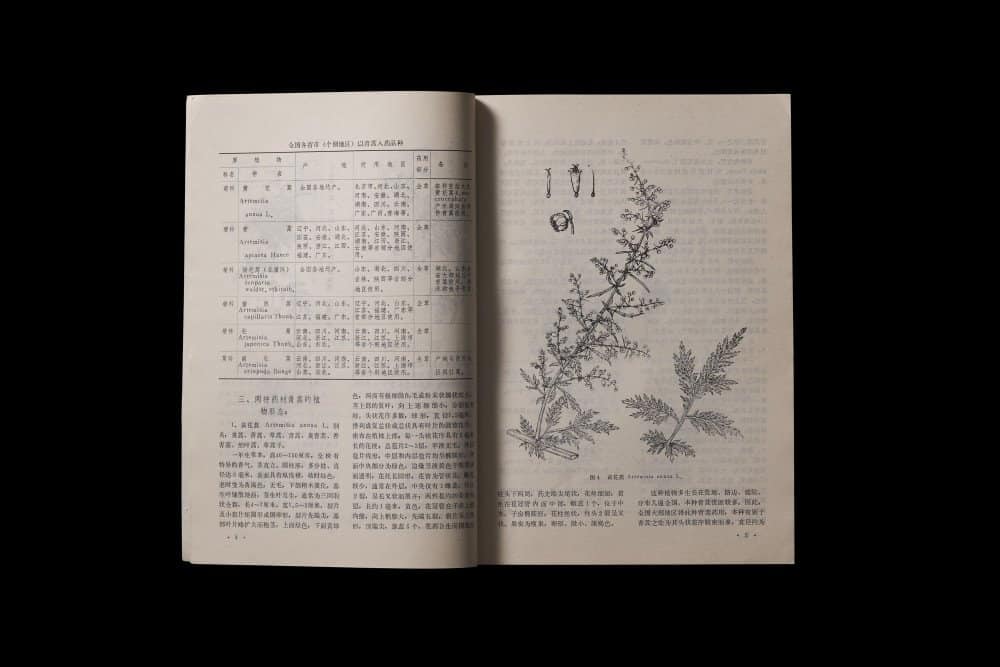

Professor Tu Youyou, being familiar with both Chinese and Western medicine, began to comb through ancient Chinese texts for a possible treatment. She came upon a 4th century herbal remedy that mentioned a substance derived from Chinese wormwood. This distilled essence claimed to alleviate a constellation of symptoms. Though the disease that produced these symptoms was unnamed, Tu Youyou recognized the symptoms as matching what we now call malaria.

But when Tu Youyou tried using extracts of the compound to treat malaria, it didn’t work. Back to the ancient text — after re-reading it closely, she tried another preparation using a solvent with a lower boiling point. This prevented the active ingredient in the wormwood from being damaged, and when she tested it on mice and monkeys, every one of them recovered. She then tested the ancient formula on people — starting with herself and her colleagues — and it worked.

Tu Youyou’s discovery led to the development of Artemisinin, first proved effective in 1972, and now the most effective treatment for malaria worldwide. Amazing that for about 1,500 years this knowledge had been “sleeping.” Despite the huge beneficial effect her discovery (or rediscovery) had, in China she was treated more or less as a functionary, and for years her name went unheralded as her findings were published anonymously.

In 2005 a visiting researcher asked who actually made this discovery and after a lot of digging her name was revealed. According to reports, when she was located in 2007 she was living and working in an old apartment building with intermittent heat and a fridge in which she used to keep her herb samples.

So, around 40 years after she first distilled the treatment she was finally recognized, and in 2015, even without having a PhD or having completed medical college, she was awarded the Nobel Prize. She called her discovery “a gift to the world’s people from traditional Chinese medicine.” Honored in 2011 by the Lasker Foundation, they said her discovery was “arguably the most important pharmaceutical intervention in the last half-century.”

How did China eliminate malaria?

Wow. No simple answer. One thing that certainly helped was the ability to mobilize a number of sectors and agencies to work together: health, of course, but also education, science, the army, police, industry, media, agriculture and even the tourism sector.

Oh, the ruthless efficiency of an authoritarian government!

Obviously there was also some spraying of stagnant ponds where mosquitoes breed, and often of people’s homes near those at-risk areas — Rachel Carson would not approve. Eventually, a less environmentally disruptive approach became available when insecticide-laced mosquito nets were introduced in the ‘80s. This was done even before the WHO recommended such nets. China decided to try them on their own. They worked — more than 2.4 million nets were distributed and infections went down. By the ‘90s they were down to 117,000! The WHO eventually endorsed and recommended them and now they’re used everywhere.

China’s most recent strategy to crush any outbreaks is a response and surveillance approach called “1-3-7.” Here’s what the numbers mean. If someone comes in with symptoms that resemble those of malaria, local medical personel must report it within one day to the nearest Chinese disease control agency, usually via SMS. Within three days the case must be confirmed or not as malaria by a health authority who can investigate in person and determine the risk of further infections in the area. And within seven days measures must be taken to both treat the patient and prevent further spread.

The 1-3-7 strategy might not have worked if China didn’t have universal health coverage, which covers about 97 percent of the population. This eliminates the hesitation people might have in getting checked if they had to be afraid of costs. It also makes quick diagnosis, treatment and containment within seven days possible. China also has good cell phone service (good enough to send an SMS, at least) even in rural areas, making it feasible to report cases within one day. So implementing this strategy in other places — like parts of Africa, for example — isn’t as simple as cutting and pasting it.

So China’s success rests on a whole raft of factors. The ability to think out of the box, as Tu Youyou did. The willingness to try new techniques like the insecticide laces nets. The ability to coordinate multiple disparate governmental sectors, from tourism to agriculture. Universal health care (not available until a few years ago!) and cell phone coverage in rural areas.

All of this makes their success hard to replicate in many parts of the world. But we can still get inspiration and learn from it. What an amazing accomplishment, and so long in coming.