A mix of alder, maple and Japanese cherry trees line Berlin’s Horseshoe Estate, a large-scale 1920s housing complex and UNESCO World Heritage site in the south of the German capital.

But according to Sebastian Herges, a 42-year-old resident of the estate, over the past few years those valuable species have begun to suffer due to Berlin’s increasingly extreme weather, which has seen summers become longer and drier and winters become wetter and stormier. “We noticed the change in weather and have not been able to sleep since then [out of concern for the trees],” he says.

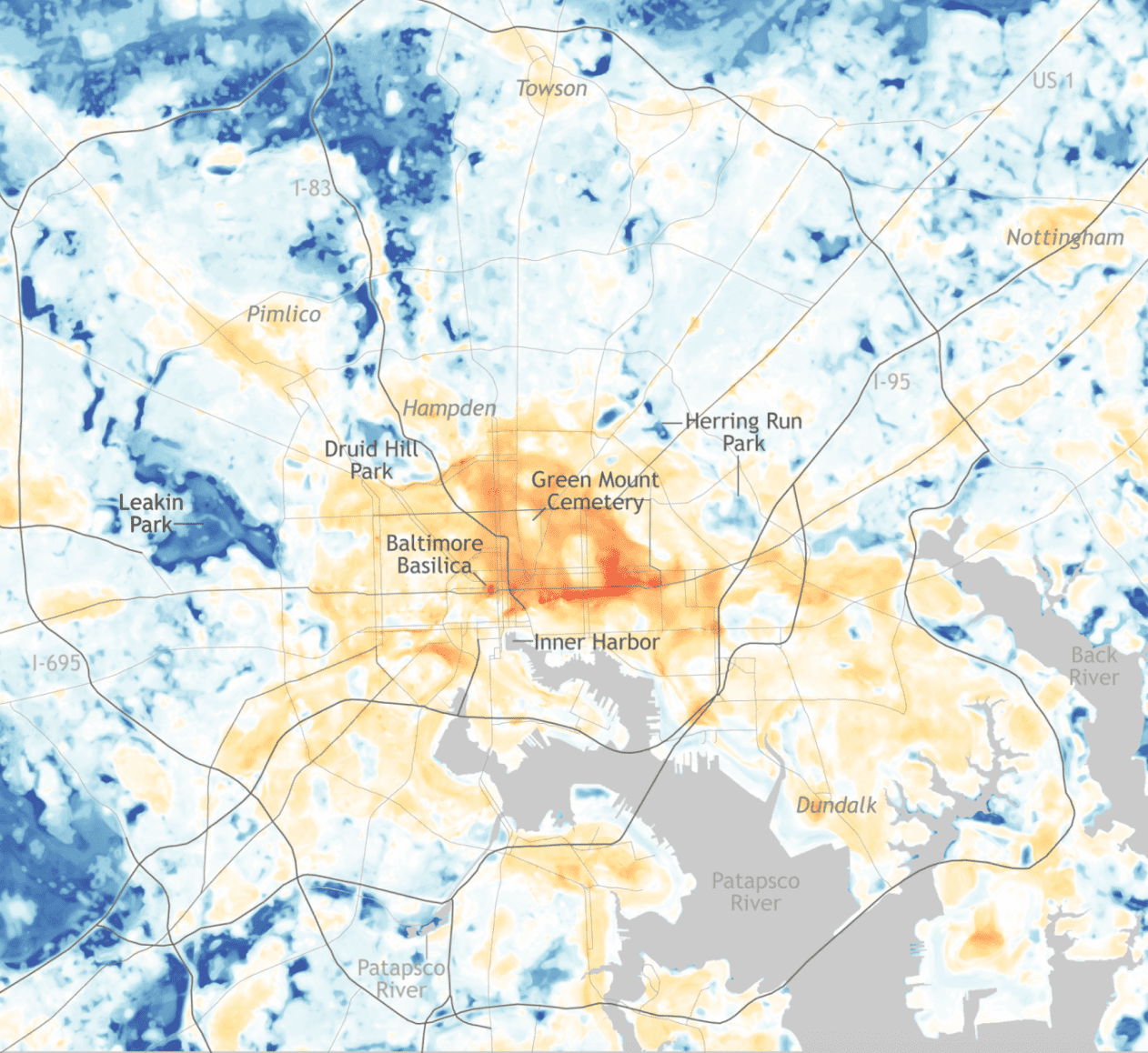

City trees like those by Herges’ home are drying up due to climate change, putting a strain on Berlin’s ecosystem. In 2018, Berlin was the sunniest city in Germany with 2,308 hours of sun, and since then there have been persistent droughts. According to Berlin city hall, there were 7,000 fewer trees at the end of 2019 than in 2016, as the heat took its toll.

To get to the root of the problem, CityLAB, a municipal body that develops cutting-edge projects for Berlin’s metropolitan area, launched a project known as Gieß den Kiez, or “pour the neighborhood,” in May 2020.

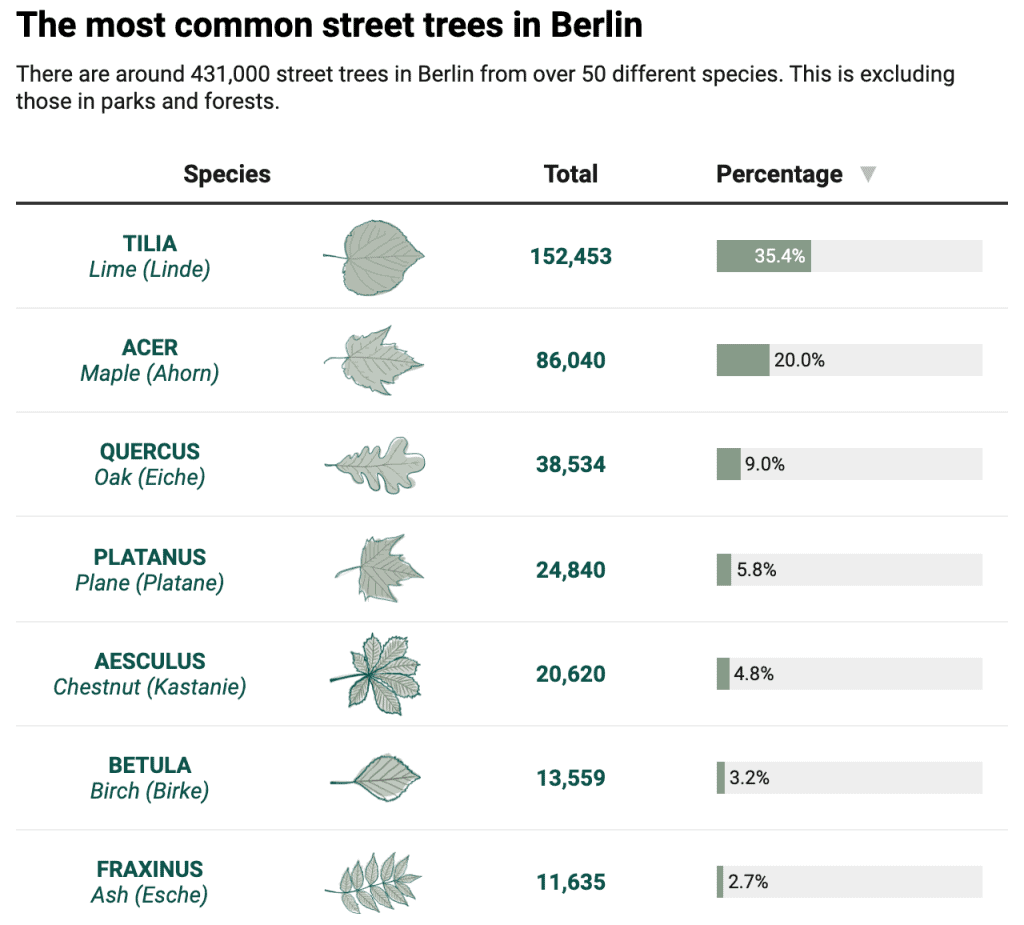

The online platform allows citizens to coordinate the watering of Berlin’s trees using an interactive map containing information on 760,000 of the city’s one million trees, including species, age and water needs (often as much as 50 liters per day), as well as how often they have been watered. The platform also instructs users on correct irrigation and the location of Berlin’s water pumps, minimizing transport and supporting the use of graywater — wastewater without fecal contamination.

The project is underpinned by an “open source” ethos, with its code published online — meaning the platform can be easily reproduced by other cities — and tools that are freely available such as OpenStreetMap, an alternative to Google Maps, and public German Weather Service data.

“Water is one resource, energy is another, as are trees,” says Julia Zimmermann, who is in charge of the Technologiestiftung Berlin-backed project. “We realized that by combining the data we had, and providing it to the public, we could help solve several problems all at once.”

More than 2,000 citizen-caretakers are now registered and actively watering trees, and over 5,000 trees have been “adopted” through a function that allows users to subscribe to specific trees. It’s providing huge savings to Berlin, since the cost of traveling to and watering each tree is estimated to be between seven and eight euros, she says.

Sebastian Herges joined as soon as the platform launched and is now one of the most active users, regularly communicating with others via the project’s Slack channel. “We decided to get involved because commitment reflects the power of society,” he says. “We consider projects like this to be indispensable, because here you learn how trees are watered. There is an educational gap that needs to be filled for everyone.”

Susan Day, professor of urban forestry at the University of British Columbia, believes projects like Pour the Neighborhood could have growing importance with the onset of climate change.

“It’s not an exaggeration to say that healthy human life depends on the vegetation that surrounds us,” she says. “It affects the physical environment through things like temperature and water quality. But it also affects your health – being exposed to nature, encouraging more outdoor activity. A city without trees isn’t very livable.”

Mature city trees store carbon and create a cooling effect that helps to reduce urban heat, adds Day, and properly watering trees could be more impactful than simply planting new ones. When trees are planted and they are young and new, they generally need watering and irrigation for years. Cities are best served when they seek professional urban forestry consultation on the kinds of tree species that are planted, the geology of the locations chosen, and the maintenance required.

“This project could be very important,” adds Professor Day.

Crushed by negative news?

Sign up for the Reasons to be Cheerful newsletter.Herges says that in the Horseshoe Estate alone there are 80 young trees, which require extra care and attention. “Yes, we can feel the effect of watering them,” he says. “Without us they would have been affected much more.”

However, scaling the project to other cities might not be straightforward. Berlin has two particularities: excellent collation and publication of data (every year authorities in each of Berlin’s 12 districts survey and measure almost every tree) and the presence of some 2,000 free water pumps around the city, a legacy from when West Berlin was isolated, in case citizens needed emergency water for drinking or fires.

Professor Day also points out that the varying geography and topographies of cities could impact the effectiveness of any citizen-led watering system. “They vary sometimes in unexpected ways,” she says. “It depends on the hydrology of the city and the species. Is there plenty of soil? If the roots of trees are confined underground, they are like a potted plant, and rely more on watering.”

Yet the open-source nature of the project means that it’s purpose-built for reuse. And already another German city, Leipzig, launched its own version this year. “Someone working for Leipzig saw the code for our project online and used it without even contacting us,” says Zimmerman. “In one and a half weeks he had it running. It proves that open source works.”